In our newly published paper, ‘A perspective on returns’, the Real Return team discusses the probability that the boom we have seen in financial markets will end in a similar fashion to those experienced in the last twenty years.

In a short series of posts, we’ll discuss some of the key ideas in the paper, beginning with where we think financial markets currently stand.

Then and now – challenges in the wake of the global financial crisis

In the aftermath of the global financial crisis in 2008, it seemed unlikely to us that we were at the start of another secular expansion in financial-asset prices; with interest rates and bond yields standing at very low levels, and corporate margins and valuations having recovered substantially, the opportunity set appeared very different from that which investors enjoyed in the early 1980s. In addition, there were many other potential triggers for volatility, including experimental monetary policy interventions, inexorably rising global debt levels and rising wealth inequality.

In combination, these factors suggested to us that the period following the crisis could be marked by increasing risk and uncertainty. When we considered the outlook in previous iterations of ‘A perspective on returns’ (in 2012 and 2014), we concluded that the strong returns seen in risk-asset markets in the years immediately following the financial crisis could easily be consistent with the boom phase of the next boom-bust cycle, as opposed to signifying meaningful economic growth.

Our perspective in 2018

Notwithstanding the bout of volatility we have seen in asset markets since the beginning of February, the bull market that began after the financial crash has continued for much longer than we had anticipated. However, the fact that the current boom is shaping up to be one of the longest on record does not necessarily mean that its underpinnings are any more stable than that of booms in the past. One could even argue the reverse – that the longer persistent interventions suppress volatility and raise risk-asset prices, the greater the risk that this perceived stability leads to greater instability in the future. This appears especially likely to us given that monetary policy has been the principal driver of asset appreciation since the financial crisis.

Investors have become increasingly conditioned to the idea that central banks will provide support and keep money cheap in times of crisis. This central bank ‘put’ was not the initial intent of policymakers, with extreme changes in monetary policy intended as short-term responses to domestic crises. However, the continued existence of these monetary policies has raised asset prices and given ‘zombie’ companies capital to function, arguably creating a deflationary impulse, rather than stoking the general (upward) pricing pressures authorities have intended to achieve.

This precedent set by the central banks, of liquidity injections in times of stress, is clearly a departure from traditional market capitalism. Without periods of capital destruction, markets struggle to allocate capital efficiently.

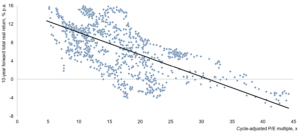

In terms of financial-market levels, valuations have become even more elevated (and therefore expected returns lower) on the back of expanding corporate margins. Indeed, a cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio (based on an average of ten years’ earnings) of 32,[1] which has only been higher in the late 1990s bubble, implies an expected inflation-adjusted return over the next ten years of approximately zero percent per annum (see chart below).

Observations over 100 years

S&P valuation level (cycle-adjusted) vs. 10-year average annual returns

Source: Prof Robert Shiller, Yale University, http://www.econ.yale.edu/~shiller/data/ie_data.xls,

Newton, 31 December 2017. Chart depicts 100 years of monthly data points.

If one takes out the effect of corporate margins, by looking at the price/sales ratio of the S&P index, we observe that the market is now at its most expensive in history. As it has previously in this expansion, this expected return profile continues to suggest to us that this is yet another extended cyclical bull market rather than a sustainable secular expansion.

[1] Source: Bloomberg, as at 15.02.18

This is a financial promotion. Any reference to a specific country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those countries or sectors. Please note that holdings and positioning are subject to change without notice.

Comments