I recently discussed with the wider investment team some interesting data on labour costs from The Conference Board, a non-profit organisation which conducts economic and business research, and I’d like to share some of the key points here.

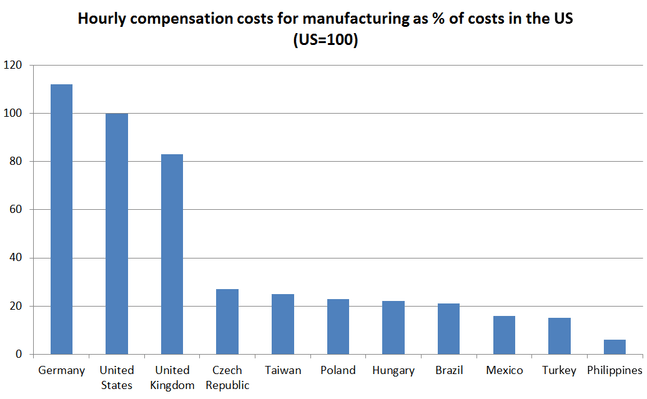

The scale of labour price gaps today is significant; the chart below shows just how expensive European and North American labour is, and how much cheaper compensation costs are in Eastern Europe, most of Asia and Mexico.

Source: The Conference Board, data to the end of 2015: https://www.conference-board.org/ilcprogram/index.cfm?id=38269

The data reported here is to the end of 2015, so further US-dollar strength since then will have further widened the gap, with US-dollar appreciation being higher than labour inflation in most cases. It’s worth noting that the depreciation of the Mexican peso in 2016 is not captured here either.

Data for China and India was presented separately by The Conference Board, owing to issues with estimations of data for the two countries. The latest data available for China (2013) showed manufacturing hourly compensation costs as a percentage of US costs at 11.3%, while the latest data for India (2012) had this figure at 4.5%.

This data is a bit out of date, so we would estimate that today the number for China is slightly higher, despite renminbi depreciation of about 12% since 2013 – so perhaps at no more than 13%, as labour inflation has eased.

By contrast, in India we expect the 4.5% figure to have fallen, with the depreciation of the Indian rupee and the credit cycle more than offsetting recent inflation. An improvement in infrastructure will be essential for countries such as India and the Philippines to unleash their manufacturing potential.

The gap in the relative costs of manufacturing between the Philippines and China demonstrates why low-end manufacturing has moved from China to the less developed countries of Asia. Meanwhile, China has moved up the value-add scale, and, as I discussed on the blog last month, is now the global manufacturing and logistics hub for pretty much every manufactured good (excluding autos).

To me, this highlights that any manufacturing with significant labour components that are hard to automate (most final assembly processes still fall into this category) is highly unlikely to move back to the US for purely economic reasons, even with a fairly hefty tariff/tax adjustment.

However, we shouldn’t discount the potential for some manufacturing to return to domestic shores for political appeasement reasons. The example of one US tech giant which I have discussed in a previous blog post offers a useful case study for the dangers of relying on media spin. While much fanfare was made about the opening of a new $150m assembly plant in the US, the company’s PR machine was far quieter about the billions being invested in China.

If manufacturing does return to the US, we believe it is likely to be highly automated – owing to such a high hourly labour rate and the falling costs of robotics. As such, we suspect this would be unlikely to act as a significant and sustained jobs stimulus.

Compared to more established economies, the value of investments in emerging markets may be subject to greater volatility due to differences in generally accepted accounting principles or from economic, political instability or less developed market practices. Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those countries or sectors.

Comments