Last week it was reported that a branch of China Minsheng Bank, China’s biggest privately owned joint-stock bank, breached internal controls in the sale of wealth management products (WMPs) to high-net-worth customers.

The RMB 3bn (US$436m) raised in the sale to some of the bank’s wealthiest private banking clients was allegedly used to plug the hole on a bill of exchange, which had been fraudulently created to cover the losses on a loan to a subsidiary of China Railway Group. The size of this alleged fraud is a useful reminder of the potential hazardous structure of China’s WMPs, which are arguably the most vulnerable area within China’s enormous financial system. It has since been reported that more of Minsheng’s clients are demanding the repayment of other WMPs they had invested in.

Non-performing loans

‘Wealth management products’ is a broad term which loosely refers to a range of on or off-balance sheet financial products marketed to customers as high-yielding (but safe) investments. They are offered via a banking system in which years of financial repression has led to negative real deposit rates, as savers have essentially subsidised the country’s huge level of fixed-asset investment.

Many investors in these products assume (naively we think) that they are akin to deposits and are thus fully backed by the sponsoring institutions, even when this may not be the case. While the products themselves can take many forms, the underlying assets generally consist of domestic corporate bonds, money market instruments, direct lending, equity investments and inter-bank deposits. Many Chinese banks admit to including non-performing loans in their WMPs as a way to hide them in off-balance sheet vehicles where accounting for loss provisioning is not required.

These products are not capitalised, and are generally not audited, which means the financial performance of the underlying investments is not transparent either to the market or to investors. Returns can be ‘juiced up’ through leverage, and are often funded in the debt and repo markets. Some WMPs even invest in other WMPs on a leveraged basis, reminiscent of the ‘collateralised debt obligation (CDO)-squared’ instruments we saw in the US structured-credit market prior to the global financial crisis.

A recent tightening of China’s money markets has led to higher market interest rates, thereby hampering the returns generated by levered products which must now pay higher interest costs on their debt, while seeing negative mark-to-market hits on their existing bond investments. The average tenor (maturity) of WMPs is four months, which means they must be continually rolled over on the basis that investors will renew their subscriptions. However, most of the assets underlying the vehicles are loans with much longer tenors, which increases the potential for significant asset/liability mismatches – just as we saw with special investment vehicles (SIVs) and conduits when they became exposed after the default of Lehman Brothers in 2008.

Ponzi scheme?

Should WMP investors decide not to roll over their funds, and at the same time new investors not be found to join the party, some of the underlying assets behind the products will need to be sold to generate cash to fund repayments, thereby catalysing unrecognised losses. This is why some refer to China’s WMPs as a Ponzi scheme. While I would expect the sponsoring bank and/or government-backed institutions to cover any such losses, should WMP investors catch wind of the problem – and be turned away en masse – the issue could become unmanageable, even with the vast resources at China’s disposal.

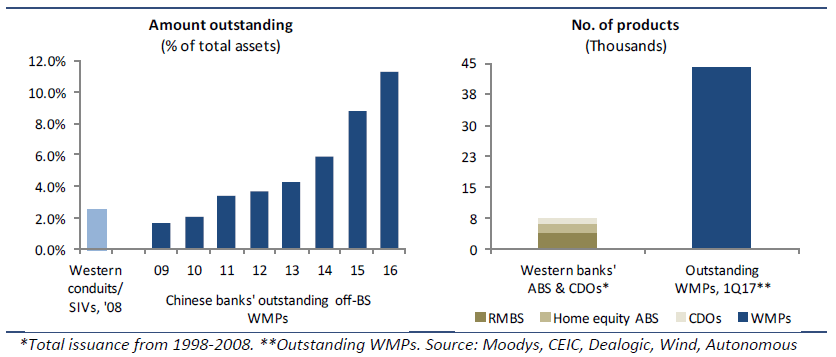

China’s WMPs have grown incredibly fast in recent years, and now amount to over 30 trillion RMB (US$ 4.3 trillion), according to Autonomous Research – which equates to JP Morgan and Citigroup’s balance sheets combined. UBS calculations are based on a wider definition of WMPs, whose scale it believes amounted to 76 trillion RMB (US$ 11 trillion) as at March 2017. Autonomous estimates that off-balance sheet WMPs (arguably where the most risky underlying assets reside) grew 49% in 2016 and now account for 89% of all WMPs outstanding. As a result, these products have become an integral funding source, backing much of China’s recent credit creation. The chart below highlights the sheer magnitude of the WMP ‘bubble’, which dwarfs the scale of the off-balance sheet issues we saw in the US mortgage market. According to Autonomous, as of March 2017, there were upwards of 44,000 WMPs outstanding, 23,000 of which fall due at the end of June 2017. This translates into 255 WMPs maturing every day, seven days a week – a huge operational task even for the most well run of banking systems!

Off-balance sheet WMPs are 4 times the size of Western SIVs/conduits in terms of assets, and there are 9 times more WMPs outstanding than Western asset-backed securities (ABSs) & CDOs

Recently, China’s regulatory bodies have released draft asset management guidelines which seek to address many of these risks, although the rules are yet to be implemented. It is worth noting that Document 82, a regulation released by the Chinese Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC) in May 2016 targeting banks’ investment receivable positions (i.e. shadow loan books which contain WMPs), has largely been unenforced.

Credit crunch

While we would welcome any move to improve regulation of these products, bring them back on to banks’ balance sheets and improve their transparency, we fear this may be too little too late. Even if China is able to avoid a calamity in this area, the curtailment of growth in WMPs from any such regulation is likely to dent the provision of credit to what remains a highly credit-dependent economy, thereby affecting China’s (and indeed the world’s) level of economic growth.

Pinpointing the timing and catalyst for a systemic WMP failure is extremely difficult, but it is clear to us that the longer these products are allowed to continue to grow exponentially, the more severe the eventual outcome is likely to be when one occurs. The problem could conceivably continue to build for many years to come, with any issues likely to be hidden away from public sight, in contrast to the US sub-prime mortgage crisis.

As global investors, we remain alert to these risks when positioning client portfolios and continue to avoid any direct exposure to China’s banking system.

Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those countries or sectors. Compared to more established economies, the value of investments in emerging markets may be subject to greater volatility owing to differences in generally accepted accounting principles or from economic, political instability or less developed market practices.

Comments