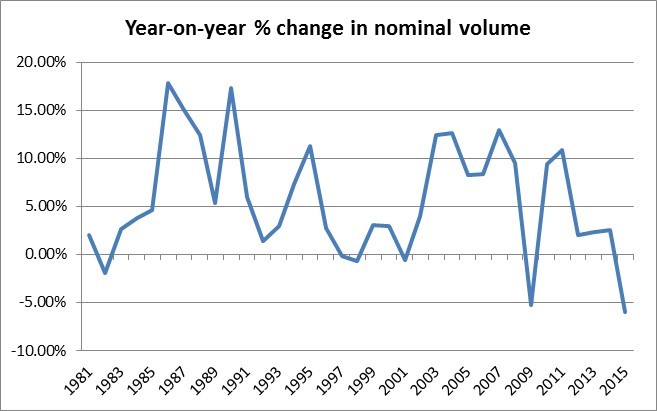

Unfortunately, it is becoming increasingly evident that the deflationary pressures exerted by the burden of too much debt, overcapacity across many industries, and technological disruption are too big in magnitude for monetary policy to counter. As the chart below shows, nominal GDP is weak.

World GDP

Source: IMF, July 2016

Private sector – not playing by the book

The policy ‘playbook’ of recent decades has prescribed monetary-policy easing as the remedy for a downturn in economic activity: lower the cost of credit to coax the private sector to borrow, and thereby boost demand and steer inflation towards target. The scale of monetary stimulus has been unprecedented – interest rates being cut to near-zero (and, in places, beyond), and vast quantities of liquidity being injected into banking systems.

But the private sector has been uncooperative. Unwilling or unable to take on the quantities of new debt necessary to overcome the structural headwinds facing the global economy, the response has been the monetary policy equivalent of ‘Can’t Cook, Won’t Cook’; the huge amounts of liquidity injected into the banking system via the bond markets through quantitative easing have effectively been a damp squib, with the ‘credit multiplier’ having failed.

Given the private sector lacks the confidence and/or ability to increase credit by the required amount, the onus falls on the public sector.

Policymaking crossroads

Policymakers find themselves at a crossroads. Should they precipitate private-sector deleveraging and an ‘Austrian’-style recession by allowing deflationary pressure to work through the global economy, or should they turn instead to the next set of expansionary policies?

The former is politically unacceptable owing to the social compact between governments and their electorates. The social upheaval of such a move would be too destabilising and amount to political suicide for any governing party behind it. As a result, we think politicians are likely to turn to fiscal stimulus – financed by central banks – to overcome the global economic malaise.

We have long thought that attempting to resuscitate economies with monetary policy would fail and ultimately contribute to the kind of political fragmentation I wrote about in a recent post, ‘Mind the gap’.

And while we do not believe that monetary financing of fiscal stimulus – or ‘helicopter money’ in the popular vernacular – will prove successful either, we see it as a significant factor for investors to weigh up.

The intellectual case for monetary financing of fiscal spending has been made, while there is growing recognition that monetary policy is unable to lift the global economy from its perceived torpor. The Bank of Japan (BoJ), for example, effectively stated so yesterday. With the move to negative rates proving, we believe, to have been an unmitigated disaster in Japan, and the BoJ beginning to run into difficulties buying Japanese government bonds at the stated rate, the central bank announced that the effectiveness of monetary policy was up for review.

There are prominent concerns (rooted in historical experience) about the potential dangers of using central banks to fund fiscal spending, namely in the form of risks around inflation. Germany’s experience with hyperinflation in the 1920s under the Weimar Republic, Japan’s hyperinflation in the 1930s when the military press-ganged the central bank into funding the war effort, and the experience of the UK and the US of inflation in the 1970s (attributed to an overbearing state) all invoke hesitancy on the part of authorities. Economic and financial-market volatility may be a prerequisite for this resistance to be overcome.

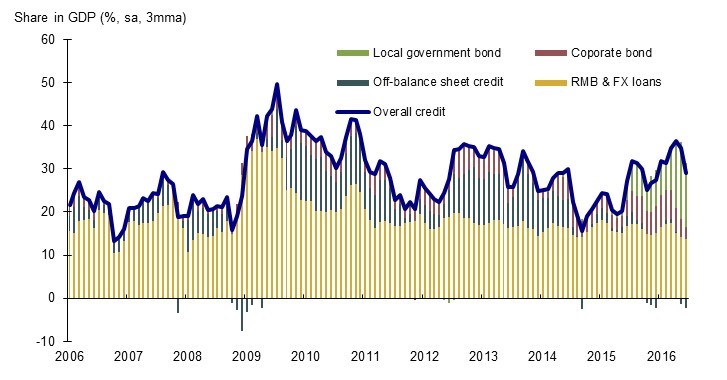

China pumps and primes

This said, we have already seen signs of debt-funded fiscal spending picking up the stimulus baton, with China, unsurprisingly, leading the way. As the Chinese economy showed mounting signs of stress last year, the authorities resorted to fiscal ‘pump-priming’. The chart below shows a rapid expansion in local government debt from mid-2015 as fiscal stimulus was ramped up.

Chinese credit

Source: UBS China Economics, July 2016

The nature of Chinese politics means that the government has a freer hand than its western counterparts to implement fiscal stimulus. However, we have already seen steps in parts of the developed world towards a closer union of monetary and fiscal policy. Growing fiscal deficits, in tandem with central-bank buying of government bonds, are monetary financing in all but name. Recent public announcements from the Bank of England and the UK Treasury have indicated a readiness to cooperate more closely than in the past as they seek to stave off an economic downturn in the wake of the ‘Brexit’ vote.

State-directed ‘business cycles’

State intervention in economies is nothing new. British Leyland was formed from nationalised British car companies in the late 1960s and received generous government subsidies. Ultimately, it destroyed the UK automotive industry, but for a time it provided employment and investment – manna from heaven for any ‘pork barrel’ politician.

Monetising of government spending on infrastructure projects could do the same now. This would be a classic form of Keynesian demand management, but ultimately we don’t think it will resolve the underlying structural issues; in fact, it would be likely to stifle further the forces of creative destruction upon which economic vitality is dependent, and could well cause stagflation (as in the UK in the 1970s) or further exacerbate deflation.

For a time, such policy could provide a strong initial boost to generate the impression of recovery. The reality, however, is that any pick-up in activity would be wholly dependent on the state continuing to push cash flows through those parts of the economy deemed to be worthy of government largesse.

To us, the fiscal ‘solution’ has worrying similarities to the economic policies that contributed to the economic malaise of the 1970s.

Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those countries or sectors. Please note that holdings and positioning are subject to change without notice.

Comments (3)

3 Comments...

This is a very useful outline of the gradual shift through the various policy tools as the democratic west struggles to cope with the overhang of their previous credit binge. Whilst I agree that demand by the private sector for fresh finance is lacklustre I wonder if it is truly a lack of demand or also a lack of supply. A full restructuring of the banking system is required

to transmit the central bank’s liquidity out into the system. In the meantime public sector led investment will be tried with mixed results. The main mechanism here is government debt funded infrastructure spending rather than propping up ailing companies as in the seventies.

This blunt tool can cause inflation problems in sectors where resources are tight whilst overall demand stays subdued until the banking system has finished re-structuring. A classic stagflation scenario. Index-lined securities that are not priced to expect central banks to reach their inflation targets could be good value.

Would you mind extrapolating a little more as to why you don’t see helicopter money working (specifically in Japan as this would likely be the first mover)? If this isn’t the cure to the current growth malaise, what is?

This is a good question, and one that I will address in greater depth in a forthcoming blog post.

To answer your question briefly, if what is meant by ‘working’ is realising an increase in economic activity and inflation then, yes, ‘helicopter money’ may indeed succeed for a time. However, history is replete with examples of governments/authorities seeking to manage the economies over which they preside, and invariably it ends in poor economic outcomes. Economies are too complex to be managed, with the law of unintended consequences never being far away to make a mockery of those that try. In reality, helicopter money is nothing more than the state attempting to manage economic outcomes. While, for a time, authorities can curate a seemingly vibrant economy, time and again it is proven to be a mirage.

Adam Smith identified the invisible hand of the market as the driver of sustainable improvements in societies’ wealth and prosperity. In a similar vein, Joseph Schumpeter outlined how economic vitality is dependent on the forces of creative destruction. If policymakers are to increase the use of monetary financing of fiscal stimulus, the likelihood is that the forces that drive economic vitality will be neutered further still. While helicopter money may prove able to realise an acceleration of economic activity, this will prove to be one built on unstable foundations with market forces inevitably asserting themselves.