15 September marked ten years to the day since Lehman Brothers filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, an event which reverberated throughout financial markets and formed the climax/nadir of what we now refer to as the global financial crisis (GFC).

Amid the chaos of a worsening subprime mortgage crisis, the US government did what few others have dared to do: it allowed a major global investment bank, Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc., to file for bankruptcy. Within days, the shock waves crippled the US’s largest insurer, exacerbated a run on money-market funds, and accelerated a cash crunch that threatened to spiral out of control.

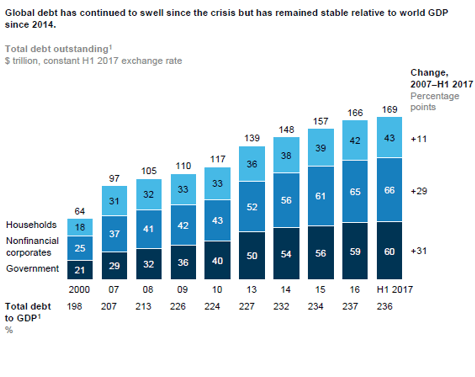

Instead of facing up to the unpleasant reality of the misallocation of capital leading up to the GFC, central banks opted for global quantitative easing (QE) – printing more money and using it to buy assets. This has, arguably, perpetuated the addiction to debt via low rates and an abundance of liquidity. Further, the collateral for the debt remains based largely upon asset values rather than on an ability to pay, much the same principle as that which characterised the housing bubble in the period leading up to the GFC. The result of all this, as the chart below shows, is global debt levels continuing to rise.

Source: Bank of International Settlements (BIS); McKinsey’s Country Debt Database; McKinsey Global Institute analysis. January 2018. For illustrative purposes only.

In fact, the latest available figures from the Institute of International Finance’s (IFF) Global Debt Monitor reveal that overall global debt rose by a further $8 billion in the first quarter of 2018 to over $247 trillion, or 318% of global GDP. [1] This has led to an over-reliance on asset prices, which is now about to be put to the test, as QE is replaced with quantitative tightening (QT) in the US, and interest rates are tentatively increased in the US and the UK. Even so, the fact that ten years after the GFC, over 25% of the global economy (by GDP) still lives under negative central-bank policy rates is indicative of the shadow that the GFC still casts. Put simply, one problem was addressed by creating others.

Stoking the populist fire?

Is it possible that the policies adopted to offset the potential impact of the GFC have contributed to the political turbulence and resurgent populism now being seen around the world? The causes of populism are still being debated, and largely revolve around inequality, globalisation, depressed wage growth and immigration issues, but did the GFC also contribute?

It could certainly be argued that, after the initial shock, global policymakers opted for a mix of extraordinarily loose monetary policy and tighter fiscal policy (especially in Europe). This reinforced the trends developed over the previous couple of decades when capital won out over labour, profits soared, and wages were cut.

This time, profits soared again, but wages stayed low and public services were cut. Austerity, then, has been a near-permanent feature of the last decade for many countries, so arguably, post-GFC policy has acted as a lightning rod to attract the more extreme politics of our day in many countries. This is backed up by the fact that support for populist parties is now at levels not seen since the pre-World War II period.

A decade on from the GFC, the long shadows from the crisis are still with us. The European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan still retain negative policy rates, which surely betrays the level of stresses that remain in the system. In fact, roughly 15% of all global bonds currently have a negative yield, while the global debt-to-GDP ratio has continually edged up to fresh record highs (as have the amounts of assets on global central-bank balance sheets) even as the US Federal Reserve slowly reduces its asset purchases.

Repeating previous mistakes?

It remains an open question whether it is actually possible to withdraw the previous ten years of stimulus without causing the next crisis. We are about to find out whether QE is the de facto new policy tool of central banks to be used in the future. If, however, QT exposes the unsustainable nature of this debt addiction, we will realise we have learnt nothing. We believe this is the more likely outcome, and, already this year, an entire opera of canaries has begun to sing in the proverbial coalmine, be it in the form of the difficult market conditions facing many low-volatility funds or the economic instability seen in Turkey and Argentina today.

Either this addiction is too hard to break, and we face a world of stubbornly high debt levels and low growth, or the withdrawal phase is about to truly set in as the world economy experiences ‘cold turkey’ as it weans itself off the debt addiction.

It is possible that we may never see another GFC in our lifetimes, but while we still have a financial system with record levels of debt, negative interest rates, unwinding QE and sky-high populism in many countries, inherent instability will remain the enduring legacy of the GFC.

[1] https://www.iif.com/publication/global-debt-monitor/global-debt-monitor-july-2018

This is a financial promotion. Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those countries or sectors. Please note that holdings and positioning are subject to change without notice.

Comments