Sterling has endured a tumultuous few weeks as fears of a ‘hard Brexit’ have grown, alongside speculation about higher food prices for consumers, reduced foreign direct investment, punishing trade tariffs and workforce shortages. UK government bonds have also seemingly borne the brunt of investor nervousness, with 10-year gilt yields now at their highest since the UK voted to leave the European Union.

However, it’s not necessarily as simple as ascribing the recent sell-off in gilts to the same cause as sterling’s marked weakness (or interpreting it as a flight from UK assets by overseas investors). We believe the context of this sell-off is an important factor to consider:

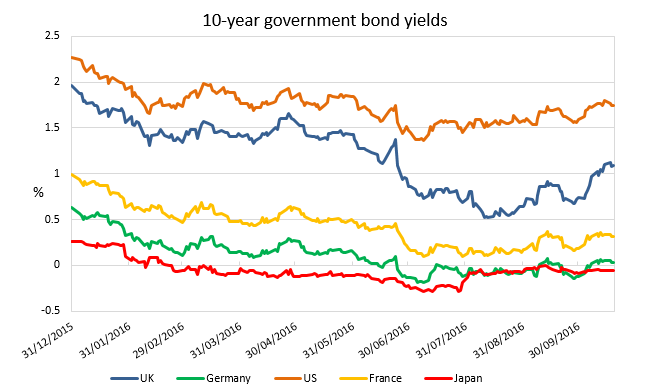

1 – The UK is not alone. As the chart below shows, other developed-world bond markets are also selling off. A number of factors are behind this: first, rising expectations of a Federal Reserve rate increase by the end of the year; secondly, growing questioning of the limits (and unwanted side-effects) of quantitative easing (QE); and, finally, discussions about the potential for governments to implement fiscal easing.

2 – Gilts had outperformed since the Brexit vote following the Bank of England’s powerful announcement in August that it would cut rates and expand its QE programme, which exceeded investor expectations. With strong hints that more would follow, the market had fully priced in another cut by year end. However, now that the dust has settled and the immediate economic impact seems modest (and with Article 50 not set to be triggered until Q1 2017), investors are questioning the need or willingness of policymakers to implement yet more easing in November or December. So, just as more rate cuts were priced into the UK gilt market, more has to be priced back out.

3 – Further rate cuts are becoming increasingly less likely, with sterling’s fall adding to inflation expectations and consequently raising the bar for an already divided Monetary Policy Committee to implement additional easing.

So, while we remain cautious on gilts, this is based on our interpretation of the future path of interest rates, rather than on the basis that a ‘sterling crisis’ is imminent.

This is a financial promotion. Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell this security, country or sector. Please note that holdings and positioning are subject to change without notice. Compared to more established economies, the value of investments in emerging markets may be subject to greater volatility owing to differences in generally accepted accounting principles or from economic or political instability.

Comments