The Suez Canal, a key shipping shortcut which carries around 12% of global trade by volume, became blocked for almost a week in late March after the Ever Given, one of the world’s biggest container ships, ran aground amid high winds. The stricken ship, and the resulting disruption to supply chains, were widely viewed as a metaphor for the challenges facing global trade, as the pandemic, growing geopolitical tensions and a rise in protectionist trade policies have contributed to a backlash against globalisation.

Financial-market participants did not appear unduly concerned by such barriers during the quarter as global-equity markets continued to make gains, appearing to price in a strong economic rebound later in the year. Although many economies remained under some form of lockdown, the first quarter of the year saw global merger and acquisition activity reach record levels as the value of deals exceeded US$1.3 trillion, surpassing even the highs seen during the ‘dotcom’ boom at the start of the millennium.1

Government-bond investors, however, experienced a brutal three months as worries over the outlook for inflation continued to grow. Much of the bond-market concern has been centred on the US, where the 10-year Treasury yield rose by around 80 basis points during the three-month period (bond yields move inversely to prices), reversing almost all of the decline seen during the coronavirus crisis.2

There are fears that the new Biden administration’s US$1.9 trillion fiscal stimulus package, which won final approval in Congress in March, may stoke inflation, especially when coupled with the unprecedented extensive monetary and fiscal stimulus already in place. Meanwhile, confidence has grown that the rollout of Covid-19 vaccines will boost economic growth, with pent-up demand having the potential to meet constrained supply as economies reopen. Nevertheless, the US Federal Reserve (Fed) signalled at its March meeting that it expected any rise in consumer prices to be temporary, and that it envisaged keeping interest rates close to zero until at least 2024.3

Rising inflation expectations affected equity markets at times during the quarter. Notably, high-profile US technology stocks experienced a sharp sell-off in the second half of February, amid fears that higher discount rates would decrease the value of future cash flows for what are perceived as longer- duration assets. Stock markets were also stirred in late March when some large global banks began selling at least US$20 billion worth of shares for a then unnamed client (subsequently revealed to be Archegos Capital Management – a family office investment vehicle run by former hedge-fund trader Bill Hwang) which had missed a margin call. The stocks involved, primarily technology and media businesses, saw their prices fall sharply. While this fire sale was clearly a mishap that is now attracting regulatory scrutiny, it could be viewed as another example of the shift taking place in equity markets away from those businesses that have benefited during the pandemic, towards more cyclical companies that are likely to perform better as economies reopen.

In fixed income, major government-bond markets all exhibited losses over the quarter. UK gilts, as represented by the FTSE Actuaries UK Conventional Gilts All Stocks Index, declined by -7.2%, while the JP Morgan Global Government Bond Index (excluding the UK) produced a negative quarterly return of -6.5% in sterling terms. Corporate bonds, as represented by the ICE BofA Sterling Non-Gilt Index, were also negative and returned -4.1% over the quarter.4

Conversely, all major equity markets delivered positive returns. UK equities produced a return of +5.2% over the quarter, while North American stocks returned +4.9% in sterling terms. Asia Pacific ex Japan equities delivered a quarterly return of +4.2%, and Europe ex UK stocks returned +2.4% in sterling terms. Meanwhile, emerging markets and Japanese equities made more muted but still positive returns of +1.9% and +1.2% respectively for UK-based investors.5

With the market narrative shifting to the overriding themes of rising real bond yields and the potential emergence of inflation, gold – which had hit an all-time peak during 2020 – took a decisive step down in the first quarter of 2021 and delivered a negative return of -10.1% in US-dollar terms (and -10.8% in sterling terms).6

On 18 February, the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) Perseverance rover made a dramatic landing on Mars after a journey from Earth of almost seven months. The rover carried a small helicopter called Ingenuity, with which NASA wants to demonstrate the possibility of powered flight in Mars’ thin atmosphere. Meanwhile, the new Biden administration’s US$1.9 trillion coronavirus relief package, agreed in March, includes what is essentially a version of ‘helicopter money’ – means-tested direct payments of up to US$1,400 for most American adults.7 This was followed by an announcement at the end of the quarter of a plan to spend a further US$2 trillion on an infrastructure investment programme, as well as raise corporate taxes.

With the Democrats having gained control of both chambers of Congress following their January victories in the Georgia run-off election, the path had been cleared for a major increase in fiscal stimulus and the budget deficit. While politicians had begun to loosen the purse strings well before the Covid-19 crisis, the scale of the stimulus represents a decisive shift away from the tighter fiscal approach that has dominated the economic narrative in the US and many other developed economies since the 1980s.

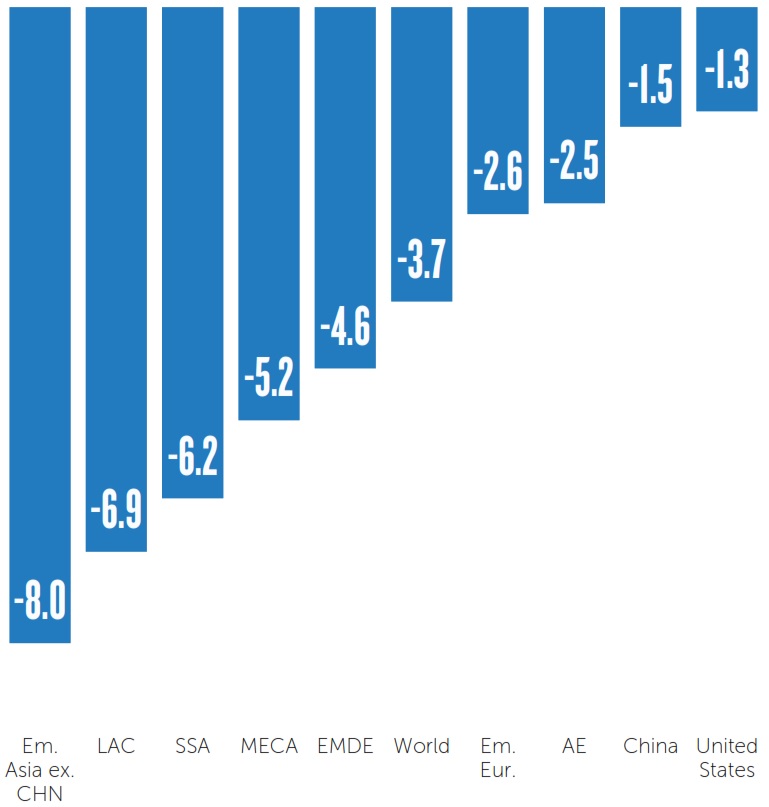

Projected 2022 GDP level relative to pre-Covid-19 (January 2020) forecast,

% difference

Note: AE = advanced economies; Em. Asia ex. CHN = emerging and developing Asia excluding China; Em. Eur = emerging and developing Europe; EMDE = emerging market and developing economies; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; MECA = Middle East and Central Asia; SSA = sub-Saharan Africa.

Source: IMF staff calculations, January 2021.

In its World Economic Outlook update in January, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicted that the US would experience a stronger recovery from the economic hit of the pandemic than most other advanced and emerging economies (excluding China). The IMF forecasts that the US economy will be only around 1.3% smaller by 2022 than it had projected prior to the pandemic.8 While this may partly be explained by the fact that other countries – such as those in Europe – have imposed stricter lockdowns on their economies, the US is also spending more on economic stimulus than most of its counterparts.

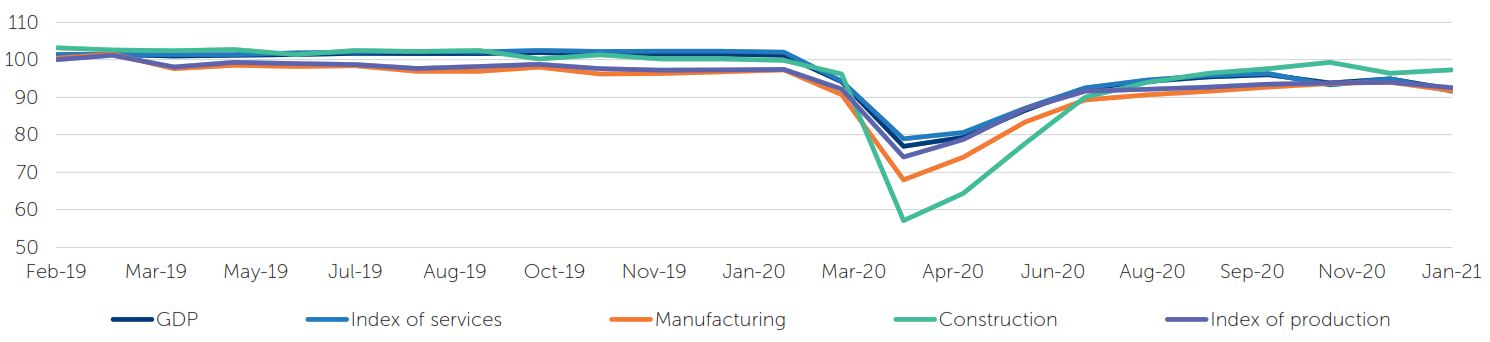

In spite of a harsh new lockdown that began early in January, the UK, which announced plans to gradually reopen its economy as its rapid vaccine programme continued, appears to have performed significantly better since the start of the year than forecasts had predicted. Data from the Office for National Statistics showed that UK GDP fell only 2.9% in January compared with the previous month.9 Many sectors that suffered hugely during the first lockdown in spring 2020, such as retail, hospitality and entertainment, have been able to adapt their business models to offer online or delivery services. The Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee upgraded its outlook for the UK’s economy at its March meeting, but, like the Fed, indicated that it believed inflation remained under control.

UK monthly GDP and components index, seasonally adjusted

Index 2018 = 100

Source: Office for National Statistics, March 2021.

On the other hand, the end of the Brexit transition period and the introduction of new trading arrangements between the UK and European Union (EU) led to a dramatic fall in the UK’s exports in January. Germany, which is the UK’s second biggest trading partner, saw its imports from the UK fall by more than 50% in January compared with the same month in 2020.10 With border disruption and increased paperwork likely to be a key factor, the UK Office for Budget Responsibility expects that conditions should ease as businesses become more accustomed to the new arrangements.

In contrast to the UK, Europe’s slow vaccine rollout and a third wave of coronavirus infections have led to renewed lockdowns and the downgrading of growth forecasts. Germany’s retail sales declined by 4.5% in January compared to the previous month, and with the eurozone’s GDP having shrunk during the fourth quarter of 2020, a likely further contraction in the first quarter of 2021 is set to signal a recession (two consecutive quarters of negative growth).

Projections from the European Central Bank (ECB) suggest that economic output will not return to pre-pandemic levels before 2022,11 and many countries – particularly those in the south of the continent that rely heavily on tourism – fear another ‘lost summer’ if vaccine delays mean they cannot reopen to visitors. In the face of the uncertain economic recovery, and as rising bond yields have pushed up the bloc’s borrowing costs, the ECB announced plans in March to step up the pace of bond purchases under its €1.85 trillion pandemic emergency purchase programme.

Data collected by Osaka University in Japan has shown that the country’s cherry blossom season, its traditional sign of spring, peaked on 26 March, the earliest date since records began in 812 AD.12 There were also signs during the quarter that Japan’s economy could bloom sooner than many of its Western counterparts as it recovers from the pandemic. Japan saw strong GDP growth in the final quarter of 2020 which meant that its output was only 1% below the corresponding period in 2019.13 As the country re-entered a Covid-19 ‘state of emergency’ in January, its recovery is likely to falter, but the relatively modest restrictions that have been imposed, which appear to have kept the virus in check, are likely to limit the economic fallout. Business sentiment has also improved, with the Bank of Japan’s quarterly Tankan index for large manufacturers rebounding into positive territory at the end of March.14

Relations between China and the major Western powers took a significant turn for the worse during the quarter as the US, EU, UK and Canada imposed sanctions over the persecution of Uyghur Muslims in China’s Xinjiang region. The Biden administration has signalled continuity with Donald Trump in terms of its willingness to confront China, and has also criticised the country on the further erosion of democracy in Hong Kong.

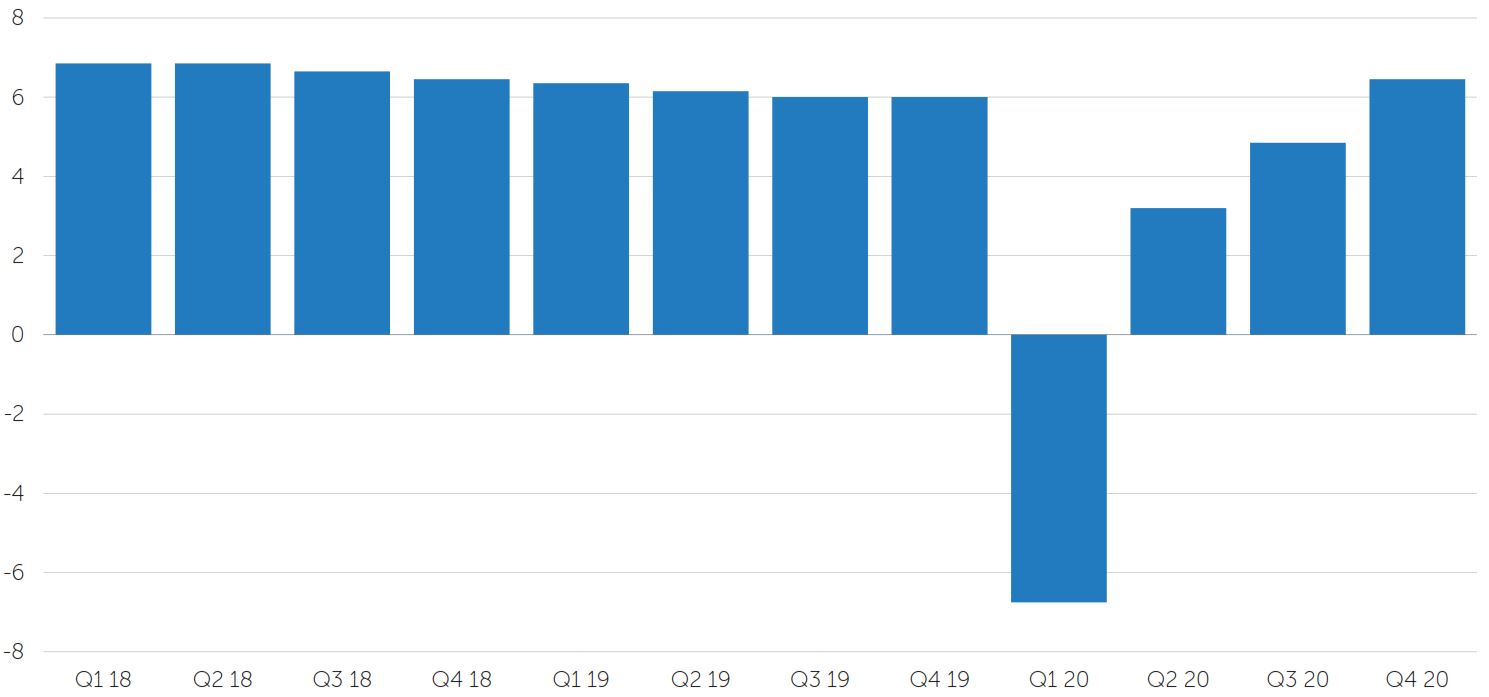

China annual GDP growth rate

% change, year on year

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China, January 2021.

Nevertheless, in a strong final quarter of 2020, China returned to its pre-pandemic growth rate and became one of the few countries in the world to deliver positive growth for the year. Premier Li Keqiang announced a 6% growth target for 2021 at the National People’s Congress in March. However, the same month saw the renminbi, which had performed strongly in 2020, experience its worst month against the US dollar since the trade war in 2019.15 With China’s debt now standing at 270% of GDP, Beijing will also need to decide if it can withdraw some stimulus measures at a time when a recovery appears to be gaining pace in other economies.

This mission is about what humans can achieve when they persevere. We made it this far. Now, watch us go.

John McNamee, project manager of the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover mission, NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory

1 https://www.ft.com/content/bacdf86f-e786-4439-966e-f5958adb1c59

2 https://www.ft.com/content/fc3f2b03-fe54-4e76-ab8a-cb402d5bfdff

3 https://www.ft.com/content/3d7704d3-a312-4294-95bc-90233f469ccd

4 Bond market returns sourced from FactSet, 01.04.21

5 Equity market returns sourced from FactSet, 01.04.21 (All sterling total returns, FTSE World Index)

6 Gold bullion returns sourced from FactSet, 01.04.21

7 https://www.ft.com/content/ecc0cc34-3ca7-40f7-9b02-3b4cfeaf7099

8 https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2021/01/26/2021-world-economic-outlook-update

9 https://www.ft.com/content/b9c22fa7-85af-468a-8228-4af53c6a687f

10 https://www.ft.com/content/7a82ec8a-bf24-4b03-9de4-a0a74713de40

11 https://www.ft.com/content/e818cea3-998f-4eef-ac0f-8f11894ac9af

12 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-56574142

13 https://www.ft.com/content/6263d776-d1c7-44bf-85d7-2b679c6f3aad

14 https://www.ft.com/content/8dc75fbe-faf4-4bdc-b96f-20417ea2f0a7

15 https://www.ft.com/content/8fee5f44-0259-4fec-bb40-5dea8cc5064d

All data is sourced from FactSet unless otherwise stated. All references to dollars are US dollars unless otherwise stated.

Issued by Newton Investment Management Limited, The Bank of New York Mellon Centre, 160 Queen Victoria Street, London, EC4V 4LA. Registered in England No. 01371973. Newton Investment Management is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority, 12 Endeavour Square, London, E20 1JN and is a subsidiary of The Bank of New York Mellon Corporation. Newton Investment Management Limited is registered with the SEC as an investment adviser under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. Newton's investment business is described in Form ADV, Part 1 and 2, which can be obtained from the SEC.gov website or obtained upon request. The opinions expressed in this document are those of Newton and should not be construed as investment advice. Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell this security, country or sector. To the extent that copyright subsists in any picture used in this document, Newton recognises the copyright therein. This material is for Australian wholesale clients only and is not intended for distribution to, nor should it be relied upon by, retail clients. This information has not been prepared to take into account the investment objectives, financial objectives or particular needs of any particular person. Before making an investment decision you should carefully consider, with or without the assistance of a financial adviser, whether such an investment strategy is appropriate in light of your particular investment needs, objectives and financial circumstances. Newton Investment Management Limited is exempt from the requirement to hold an Australian financial services licence in respect of the financial services it provides to wholesale clients in Australia and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority of the UK under UK laws, which differ from Australian laws. Newton is providing financial services to wholesale clients in Australia in reliance on ASIC Corporations (Repeal and Transitional) Instrument 2016/396, a copy of which is on the website of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, www.asic.gov.au. The instrument exempts entities that are authorised and regulated in the UK by the FCA, such as Newton, from the need to hold an Australian financial services license under the Corporations Act 2001 for certain financial services provided to Australian wholesale clients on certain conditions. Financial services provided by Newton are regulated by the FCA under the laws and regulatory requirements of the United Kingdom, which are different to the laws applying in Australia. 'Newton' and/or the 'Newton Investment Management' brand refers to Newton Investment Management Limited.