At the start of July, we saw the imposition of 25% US tariffs on $34bn of imports from China, with US duties on another $16bn of Chinese goods to be added following a three-month consultation period. Beijing has committed to retaliate with a commensurate response – either quantitatively or qualitatively.

Recent White House backtracking on China-specific investment restrictions, partial lifting of Chinese tech giant ZTE’s trade ban, and last week’s approval of JP Morgan as a China-Hong Kong Bond Connect market maker[1] represent some form of compromise from both sides. Nonetheless, Chinese equities have continued to tumble since late May when US President Donald Trump confirmed $50bn of bilateral tariffs would follow those multilateral duties announced on aluminium, steel, washing machines and solar panels earlier in the year. Meanwhile, the Chinese renminbi recently suffered its sharpest depreciation since the removal of the US-dollar peg in mid-2015.

Low initial impact but…

The initial direct economic impact from these tariffs appears minimal. Metal exports to the US are less than 3% of total exports even for Canada and Mexico, while, for China, the latest levies are expected to knock only 0.1-0.2% off GDP growth. However, the subsequent announcement of planned tariffs on an additional $200bn of Chinese imports and the prospect of 25% duties on autos, including against the European Union and Japan, could have more material consequences for growth and risk appetite.

The US and China are predominantly domestically driven economies (exports are only 10% of GDP in the US and 20% in China), but, for the latter, this exogenous headwind compounds the policy-induced economic slowdown attributable to Beijing’s deleveraging focus. Moreover, while China’s manufacturing purchasing managers’ index (PMI) data continues to reflect growth (with a reading of 51.0 at the end of June), new export PMIs point to weaker trade momentum even before the latest round of tariffs. Beijing’s policymakers have begun to respond, with the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) offering rhetorical support for the renminbi, and recent targeted reserve requirement ratio cuts for major banks indicating a more nuanced approach to deleveraging.

There is considerable overlap between what China needs and what the US exports –electronics, oil, autos, aircraft and agricultural produce in particular. Furthermore, China’s prior efforts to reduce US auto tariffs, increase soya imports, improve patent regulations and liberalise financial markets (where the US retains considerable comparative advantage) all suggest there is still scope for compromise should the US administration’s more egregious threats prove a flexible tool (perhaps to be amplified during mid-term elections) in its ‘maximum pressure’ strategy.

The likelihood of the White House achieving its stated bilateral deficit-reduction target is somewhat questionable, particularly in the context of historically low US unemployment and increased fiscal spending. US Treasury Secretary Mnuchin’s targeted 35-40% increase in agricultural exports to China this year (approximately $6bn) and a doubling of energy exports (worth another $14-15bn) over the next three to five years falls a long way short of the magical $200bn mark. Were it not for the recent boom in US oil exports, we believe the US’s current $46bn trade deficit would look notably worse.

US-China tensions to persist

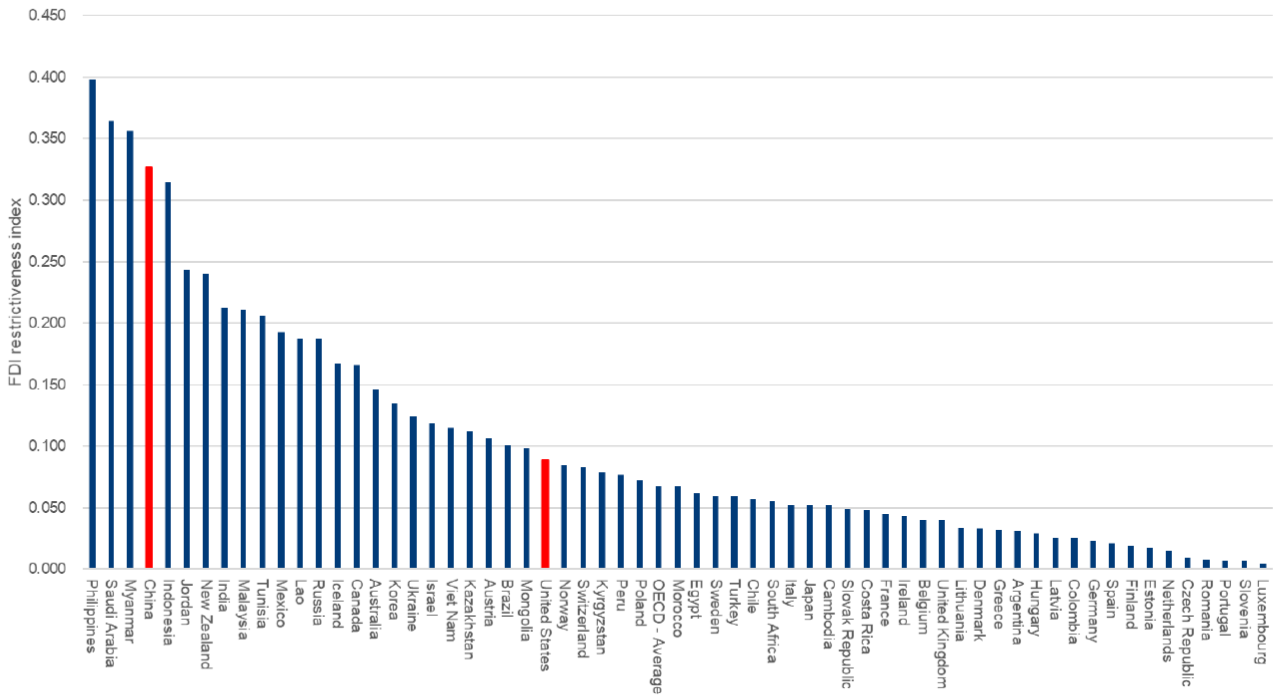

US-China tensions (both economic and geopolitical) are likely to be a more permanent feature of the investment backdrop, which the market is now beginning to price in. Although China reduced its sectoral ‘negative list’ last month, the chart below reveals that the country remains particularly restrictive and selective when it comes to foreign direct investment (FDI). Moreover, President Xi’s flagship ‘Made in China 2025’ policy appears to have convinced both sides of the US political establishment of the limitations of ‘constructive engagement’ and the challenge China poses.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) restrictiveness index

Source: OECD comparative FDI restrictiveness index, 2016

China’s rise

‘Made in China 2025’ targets a +50% domestic market share in high-tech products such as supercomputers and industrial robots – underpinned by massive state support, including $330bn of subsidies. It is a cornerstone of China’s efforts to follow its North Asian neighbours (Japan and South Korea) in escaping the ‘middle-income trap’, while enhancing its military capabilities.

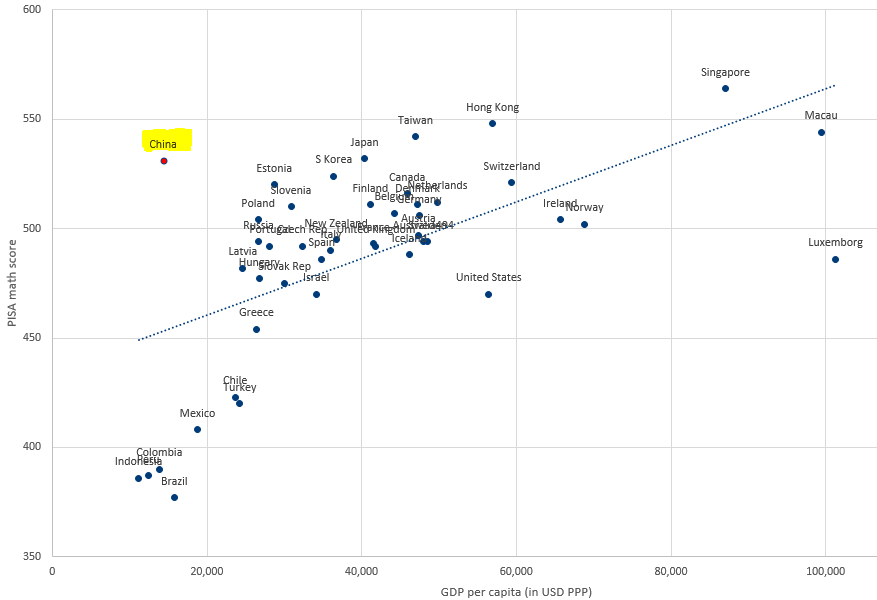

China’s high educational standards in terms of mathematics, and relatively low GDP per capita, as shown in the Programme for International Student Assessment maths scores versus GDP per capita chart below, represent a significant high-skilled/low-cost threat not just to the US, but to the competitiveness of many other developed economies. Indeed, high-tech manufacturing economies such as Germany and South Korea are particularly exposed to its rise over the long term.

PISA maths scores versus GDP per capita in USD purchasing power parity (PPP)

Source: PISA and World Bank, 2016

This is not to exaggerate China’s competitive ascendency. As our global technology analyst, Fati Naraghi, points out, the threat of disruption from China has been prevalent in the global technology sector for over 15 years, with different subsectors having seen significant disruption over time – most notably the telecommunications equipment sector in the mid-2000s. Select semiconductor stocks have remained immune, however, and global software and cloud/internet companies are expected to remain so.

China is not yet a tech leader. While its advanced tech exports continue to rise, most of these exports are by foreign firms located in China. Moreover, according to Gavekal, developed-market economies still dominate the patent revenue space: China earns just 5 cents for every $1 of international royalties it pays out; the US earns $3 for every $1 of royalties spent. That said, in new areas such as artificial intelligence (key to future military supremacy) and 5G, some Chinese firms appear to be making significant progress.

Shift in attitudes

Although we may not have witnessed a recent step change in China’s technological competitiveness, we do appear to have seen a shift in US political attitudes not solely attributable to the rumbustious White House incumbent. Persistent US-China friction is a reality to which the market is beginning to adjust. This reinforces our cautious stance towards emerging-market sovereigns and general risk assets amid tightening global liquidity.

So far, the direct economic impact of tariffs remains minimal, and China’s continued financial liberalisation and related-index inclusion (supported by recent commitments on future bond settlement standardisation) are likely to offer support to China’s government bonds and the renminbi over the coming 12 months. Although unilateral US actions undermine the international infrastructure (such as the World Trade Organisation) it helped create, China remains eager to fill the void from US institutional disengagement. This is demonstrated by its commitment to ‘One Belt One Road’ and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, as well as by its leadership of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. US aggression is also pushing Beijing towards greater diplomatic engagement with the European Union and Japan.

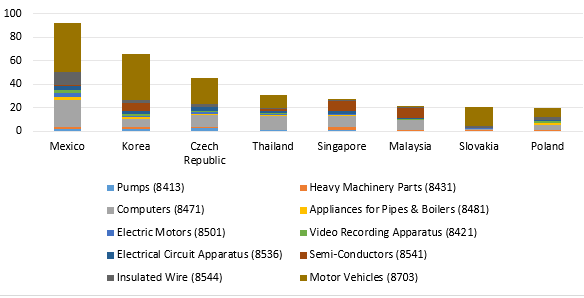

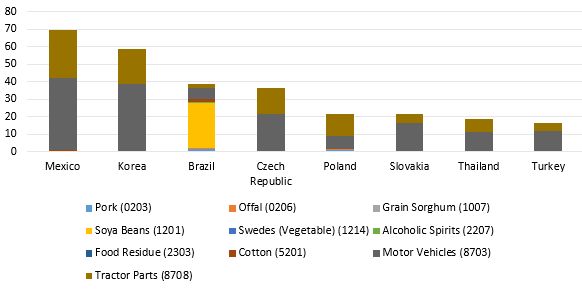

Moreover, as the below charts illustrate, some emerging markets may prove beneficiaries of import substitution resulting from the latest US-China bilateral duties.

Exports by emerging markets of the goods subject to US tariffs on imports from China (US$bn, 2017) – ten largest broad categories

Source: Capital Economics, 2018

Exports by emerging markets of the goods subject to China tariffs on imports from US (US$bn, 2017) – ten largest broad categories

Source: Capital Economics, 2018

[1] http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201807/03/WS5b3b380aa3103349141e0724.html

Comments