We assess central banks’ latest strategies on interest rates as near-term inflation continues to rise.

Key points

- Major-market central banks are dragging their feet on raising interest rates, while some relatively smaller central banks are pushing ahead with rises.

- The bigger economies are preferring to focus on slowing their quantitative-easing (QE) programmes.

- The Fed gave itself flexibility by saying that the pace of the reduction could increase or reduce depending on data, i.e. how transitory inflation turns out to be.

- Both the US and UK have seen sharp rises in near-term inflation rates, and pressure to raise rates could grow.

- The risk is that the Fed is forced to move more quickly than it currently anticipates, meaning that front-end yields remain vulnerable.

We appear to be witnessing an evolving trend where major-market central banks are dragging their feet on raising interest rates at a time when some relatively smaller central banks are pushing ahead with rises.

Faced with the prospect of higher near-term inflation, the US Federal Reserve (Fed), the European Central Bank, the Bank of England (BoE) and the Bank of Japan all decided this month not to raise rates at this point, preferring instead to focus on slowing their quantitative-easing (QE) programmes. Meanwhile, in countries that have relied less on QE, we are seeing a dramatic shift upwards in cash rates.

Fed’s worst-kept secret

Three weeks ago, we saw the US Federal Reserve announce its ‘worst-kept secret’ – that tapering of the US’s quantitative-easing programme would begin this month with a $15bn cut to asset purchases. It plans to cut by a further $15bn every subsequent month, ending the programme by June next year.

However, the Fed gave itself flexibility by saying that the pace of the reduction could increase or reduce depending on data, i.e. how transitory inflation turns out to be. The Fed has thus taken its first baby steps on the path to hawkishness but remains well behind its peers north of the border (the Bank of Canada), across the ocean (the Bank of England), and down under (the Reserve Bank of New Zealand), so patience is still very much the watchword.

Currently, data in the US is picking up again, with the Institute of Supply Management (ISM) Services Index hitting an all-time high a few days ago, and ten-year inflation expectations in the US remaining above 2.5% (the Fed’s unofficial target for ‘hot’ inflation). The risk remains that the Fed is forced to move more quickly than it anticipates, meaning that front-end yields remain vulnerable. The US dollar would be likely to be the main beneficiary in this scenario.

Pressure grows on BoE

Meanwhile, the Bank of England surprised investors at its meeting on 4 November by not raising rates. What it did do was to keep the idea of higher rates very much alive by hinting that an increase was imminent. The BoE would prefer to wait a little longer for further information on the labour market, which seems logical to us given that furlough payments have only recently ended, and it may take a couple more months yet for the effects of that to be visible.

The decision went against the market’s near-term expectations largely because, like the Fed, the BoE believes the inflation rise is temporary. More importantly, with the labour market in a state of flux, it can possibly afford to wait a little longer before it must react. Again, this appears similar to the Fed’s view, but with UK consumer price inflation (CPI) hitting 4.2% in October, up from 3.1% in September (and its highest level in a decade), pressure on the BoE to raise rates in December is likely to grow.

Elsewhere, the picture is more mixed.

The Czech central bank was the latest to shock investors with a large increase in rates earlier this month, lifting its key rate by 1.25% to 2.75%. Other countries that have been raising rates recently include Canada, New Zealand, Russia, Brazil and Poland, while Australia has stepped away from manipulating the front end of the curve.

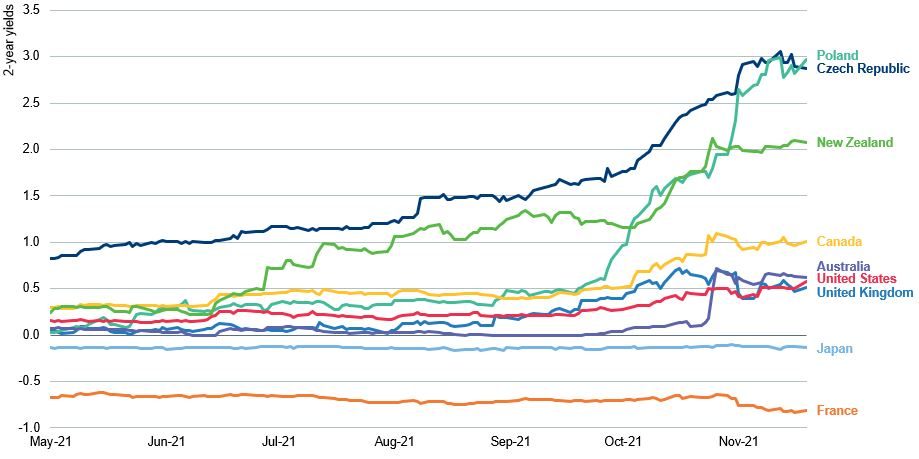

The chart below highlights the significant moves we have seen in some countries’ two-year borrowing costs and the relative stability of UK, US, European and Japanese rates. While the group of rate-rising markets is smaller than the ‘on-hold’ group, the fear is that action to date is a precursor to what could come next; the potential speed and magnitude of the moves are clearly not priced into risk assets.

Two-year bond yields 22 May – 22 November 2021

Source: Bloomberg, 22 November 2021

This is a financial promotion. These opinions should not be construed as investment or other advice and are subject to change. This material is for information purposes only. This material is for professional investors only. Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those securities, countries or sectors. Please note that holdings and positioning are subject to change without notice.

Comments