Key points

- The escalating rift between the US and China could have far-reaching effects on global capital flows and trade.

- We believe that studying private-markets data and cross-border capital flows, as well as qualitative evidence, can enhance our understanding of the implications of recent investment trends in China.

- We do not believe that companies and investors will walk away from China, but a cautious and nuanced approach is warranted with an eye toward diversifying risks.

Against a backdrop of the great power competition—a strategic competition between powerful nations over trade, technology, finance, resources and security—investors have recently witnessed Western capital gradually, but steadily, shift away from China as companies have diversified supply chains and struggled to navigate rising tensions between the world’s two biggest economies. The trend accelerated in 2023, raising the question of whether a more complete decoupling of the two economies is a real possibility. While most economic movements have revolved around supply-chain resiliency—meant to help avoid Covid-era interruptions and inventory hiccups—many investors wonder if some multinational corporations selling into China’s domestic economy and its burgeoning middle-class consumer market will also retreat amid continuing geopolitical tensions.

We believe that studying private-markets data and cross-border capital flows, as well as qualitative evidence, can enhance our understanding of the implications of recent trends. Furthermore, we believe that investors can best unlock idiosyncratic opportunities and avoid risks in this arena through active management and deep, fundamental research.

Geopolitical tensions lead to China retreat

US and China trade war

Thus far, the economic decoupling between the US and China has largely been the result of a six-year trade war marked by tariffs on hundreds of products; the US government has also attempted to lure manufacturing jobs back to the US through tax cuts and other incentives.

A push by Western governments, largely led by the US, to restrict investment into China in areas including artificial intelligence, quantum computing and semiconductors has made companies and investors rethink China plans rather than face political or reputational backlash back home. Governments are also restricting companies from selling some of their most advanced technology to Chinese customers in a bid to hamstring China’s ability to catch up. Western companies and financial firms alike have moved to curb or ringfence their activities in China in an effort to contain the risks.

China has responded to US tariffs with tariffs of its own, imposing recent retaliatory export controls on key high-technology manufacturing materials, of which they control most of the global supply. It has also reduced its direct holdings of US Treasury bonds by hundreds of billions of dollars since the trade war began, another sign the two economies are moving further apart.

How does foreign direct investment respond?

Leading US venture capital firms, Sequoia Capital and GGV Capital, have both split off their Chinese businesses into independent firms. GGV’s US partnership plans to primarily invest in companies located in North America, India, Europe, Latin America and Israel.1 Others are likely to follow suit as US limited partners in these funds now shy away from association with investments in China.

The shift is illustrated at a macro level by the reversal of foreign direct investment (FDI) into China. After over two decades as one of the main destinations of foreign investment, FDI has plunged in the last year, and China is now experiencing net foreign investment outflows for the first time since it began compiling the data in 1998. Investors have also been retreating from China’s stock markets—so much so that 2023 could be the first year that foreign investors are net sellers of Chinese equities since China opened a direct trading link in 2016.2

Some outflows are in response to political pressure from Western governments, but China’s weak post-Covid economic recovery and erratic policies have also soured sentiment among foreign multinationals.

Multinational companies in China

The country’s property market, the primary store of wealth for the majority of the population, has been in a prolonged downturn, consumer prices are teetering on deflation, and local-government debt levels continue to be a concern. There have also been several raids on Western multinational companies operating in China, including on due-diligence firms, making it more difficult to get insight into companies and potential investments in the country, further damaging investor sentiment and straining the economic relationship between the US and China.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has led multinationals to seriously consider the threat of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, a conflict that was unthinkable just a few years ago. Companies are putting contingency plans in place for a potential Taiwan crisis, including moving production out of China or trying to insulate global operations from potential disruption.

To be sure, some of these trends could reverse as political and economic winds shift; foreign capital leaving China based on interest-rate and currency arbitrage could start flowing back, and companies may start reinvesting in China if there are signs growth is improving and the business environment gets better.

China’s role in supply chains

It is unlikely China’s critical role in global supply chains will be displaced any time soon. China has significant competitive advantages due to the concentration of its manufacturing capabilities, integration of upstream and downstream suppliers, well-developed logistics and large skilled labour force, making it difficult for companies to shift away from the country. Despite weaker capital flows, China’s trade balance has remained resilient, and the country continues to run a large trade surplus (over the medium term, however, trade patterns tend to follow investment patterns, which suggest a weakening of China’s trade surplus).

While China has recently been dethroned as the US’s largest trading partner—Canada and Mexico have traded more with the US in 2023—Chinese companies are taking advantage of this shift themselves. The country’s manufacturing firms are building factories and investing in facilities in Mexico, India and other parts of Asia to continue to sell to multinational clients. Even as Mexico benefits from its proximity to the US market, China’s exports to Mexico have grown. Raw materials, components and equipment can still originate in China with final assembly occurring in Mexico. As a result, US companies may ultimately remain reliant on Chinese suppliers.

Implications and opportunities

Self-sufficiency and shaping innovation economies

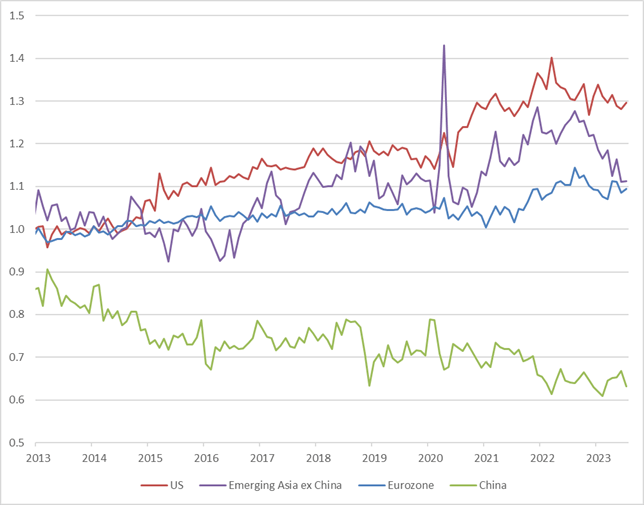

As geopolitical tensions rise and China increasingly becomes excluded from investment and technological innovation by developed economies, it is responding by reorienting its economy to be less reliant on imports and is encouraging indigenous innovation to close the technology gap with the West. The beginnings of this can be seen in the graph below, which highlights China’s declining ratio of imports to industrial production.

Ratio of imports to industrial production (2013-2023)

China’s effort to elevate and expand BRICS (an intergovernmental organisation comprising Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), the Belt and Road Initiative, and its ‘Dual Circulation Strategy’ suggest the country is planning for reduced trade with, and investment from, the West. As China’s trade with the US and Europe declines, it is filling the gap with increased trade with Russia, Brazil and Southeast Asia.

But China is not only looking outward to fund further innovation. With the slowing flow of capital from Western investors, the Chinese government and other domestic investors have an opportunity to fund innovation themselves. The decline in support from the US toward Chinese start-ups in the form of both capital and technological expertise could compel China to further foster domestic innovation and self-sufficiency. This bifurcation could lead to distinct technological spheres with separate standards, potentially raising concerns about global technological interoperability. Chinese chip companies are buying more equipment from Chinese suppliers, and technology firms are in turn starting to purchase local chips to fill their data centres. Additionally, China is planning a new state-backed investment fund that aims to raise $40 billion for its semiconductor industry—a sum larger than two other funds launched by the same group in prior years.3

However, despite these efforts, China could find it difficult to keep pace with innovations in leading-edge technology, especially if trade and investment barriers continue to rise. Heavy-handed regulation and increasing government influence in the economy also make it challenging for Chinese entrepreneurs to build truly innovative companies.

The local venture capital (VC) market has exploded in the last two decades, but it remains that US VC has played a key role in funding innovative Chinese companies—most major consumer technology companies to emerge from the country have had backing from US capital. This could further exacerbate challenges faced by Chinese technology start-ups, which may struggle to raise capital and expand globally, impeding their ability to compete on the international stage. Chinese VC funds could also strengthen partnerships with local governments, potentially aligning investment strategies with government initiatives in key sectors. It is also possible that there could be an impact on valuations for Chinese start-ups in subsequent funding rounds; the altered investment landscape, namely a decrease in foreign capital, could lead to more conservative valuations and affect overall market dynamics.

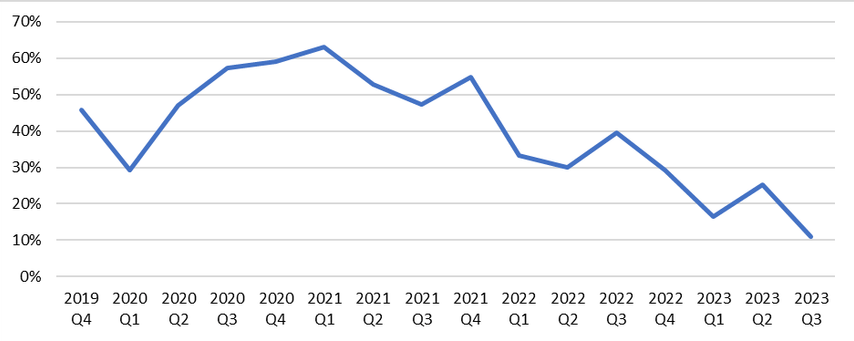

China’s state-led funding ecosystem presents its own challenges, and Chinese entrepreneurs that found success working with US VCs may not see their departure as a boon for the local economy. The shift is already in full swing as the share of US VC dollars as a portion of all foreign capital invested in Chinese companies has fallen from over 50% in 2021 to almost 10%, according to data from Pitchbook. The US’s share of global venture funding to Chinese companies has been trending downwards since early 2021, and more recently, certain large VC firms have formally cut ties with China.

US share of global venture funding to Chinese companies

These shifts could initiate a reconfiguration of the global economy, as well as a reconsideration of investment channels. The Chinese government may be compelled to open alternative channels for domestic investors, lessening its heavy reliance on the property market and life insurance products and diversifying away from investment and export-driven economic growth in favour of a foundation built on domestic consumer demand.

What it means for other emerging markets

The West’s de-risking or decoupling from China certainly creates challenges, but it also introduces opportunities for emerging markets such as India and those in Southeast Asia and the Middle East. As investors seek new growth markets in alternative destinations, these regions stand to benefit from increased trade and investment flows. Mexico and India are already benefiting as companies diversify their supply chains, as they attracted four times more investment in new offices and factories than China in 2022.4

US venture capital investors that previously looked to China for the next technology unicorn are increasingly flocking to South Asia, Southeast Asia and the Middle East for the next opportunity, though it may be challenging to find companies that can scale like China’s technology titans. These emerging markets may witness a noticeable uptick in foreign investment, leading to an accelerated growth in their technology sectors.

Thus far, other emerging markets have not been forced to pick sides amid US-China tensions, but this could soon change. Chinese companies have long been major investors in Southeast Asia, the Middle East and other emerging markets, and this investment is expected to continue.

Chinese VC funds are also considering these markets for opportunities in their hunt for high returns—in some cases, Chinese VCs are hoping to fund start-ups based in other countries but run by Chinese entrepreneurs. Furthermore, with US VC firms spinning off their China arms, the new firms have more freedom to pursue investments abroad. Despite geopolitical tensions and restrictions, some have speculated whether Sequoia Capital’s split will allow its Chinese arm, HongShan, to ramp up investments in US-based start-ups, raising new questions about the flow of Chinese money into American technology.5 It is possible Chinese VC funds that intend to expand globally may face challenges given geopolitical tensions and increased scrutiny over cross-border investments, potentially affecting their ability to participate in international deals.

Navigating the future

The escalating rift between the US and China could have far-reaching effects on global capital flows and trade. We do not believe that companies and investors will completely walk away from China, but a cautious and nuanced approach is warranted, with an eye toward diversifying risks. Most experts also think the risk of conflict over Taiwan could increase over the coming years, which could force a full decoupling. These changes create challenges, but also open the door for new investment opportunities. While both the great power competition phenomena and economic decoupling of China and the West is expected to play out over decades, this event has current implications, allowing investors to unlock opportunities presented by this dislocation.

[1] Reuters. 21 September 2023. https://www.reuters.com/markets/us/us-venture-firm-ggv-capital-separate-china-business-amid-geopolitical-tension-2023-09-21/

[2] Bloomberg. 23 October 2023. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-10-23/why-global-investors-are-exiting-china-unloading-stocks

[3] Reuters. 5 September 2023. https://www.reuters.com/technology/china-launch-new-40-bln-state-fund-boost-chip-industry-sources-say-2023-09-05/

[4] The Wall Street Journal. 3 November 2023. https://www.wsj.com/economy/trade/economy-us-china-tariffs-trade-investment-1c58d24e?st=kq9umz3gxusxl7p&reflink=desktopwebshare_permalink

[5] The Information. 7 November 2023. https://www.theinformation.com/articles/american-ai-startups-raise-money-from-top-chinese-vc-firms-including-sequoia-capital-china

This is a financial promotion. These opinions should not be construed as investment or other advice and are subject to change. This material is for information purposes only. This material is for professional investors only. Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those securities, countries or sectors. Please note that holdings and positioning are subject to change without notice. Analysis of themes may vary depending on the type of security, investment rationale and investment strategy. Newton will make investment decisions that are not based on themes and may conclude that other attributes of an investment outweigh the thematic structure the security has been assigned to. Compared to more established economies, the value of investments in emerging markets may be subject to greater volatility due to differences in generally accepted accounting principles or from economic, political instability or less developed market practices. This article was written by members of the NIMNA investment team. ‘Newton’ and/or ‘Newton Investment Management’ is a corporate brand which refers to the following group of affiliated companies: Newton Investment Management Limited (NIM), Newton Investment Management North America LLC (NIMNA) and Newton Investment Management Japan Limited (NIMJ). NIMNA was established in 2021 and NIMJ was established in March 2023.

This material is for Australian wholesale clients only and is not intended for distribution to, nor should it be relied upon by, retail clients. This information has not been prepared to take into account the investment objectives, financial objectives or particular needs of any particular person. Before making an investment decision you should carefully consider, with or without the assistance of a financial adviser, whether such an investment strategy is appropriate in light of your particular investment needs, objectives and financial circumstances.

Newton Investment Management Limited is exempt from the requirement to hold an Australian financial services licence in respect of the financial services it provides to wholesale clients in Australia and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority of the UK under UK laws, which differ from Australian laws.

Newton Investment Management Limited (Newton) is authorised and regulated in the UK by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), 12 Endeavour Square, London, E20 1JN. Newton is providing financial services to wholesale clients in Australia in reliance on ASIC Corporations (Repeal and Transitional) Instrument 2016/396, a copy of which is on the website of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, www.asic.gov.au. The instrument exempts entities that are authorised and regulated in the UK by the FCA, such as Newton, from the need to hold an Australian financial services license under the Corporations Act 2001 for certain financial services provided to Australian wholesale clients on certain conditions. Financial services provided by Newton are regulated by the FCA under the laws and regulatory requirements of the United Kingdom, which are different to the laws applying in Australia.

Comments