Key points

- The agricultural industry is estimated to contribute approximately 18% of global carbon dioxide equivalent emissions annually, and biochar is one of many promising solutions for addressing agricultural and land-use emissions.

- Biochar has many applications, the primary one being to store carbon sequestered by biomass which would otherwise be re-released into the atmosphere.

- Despite the clear benefits of biochar, there are a number of challenges to expanding its adoption.

- When we engage with companies that are reliant on agricultural produce, it is helpful for us to be informed about the range of options available that make it possible for them to improve their environmental footprint.

Innovative solutions for reducing or sequestering carbon emissions are continuously emerging, and one thing we have learned is to be open minded, because there is no one silver bullet for reducing emissions – it is going to require a myriad of approaches specific to the sector and application in question. Taking the agricultural industry as an example, it is estimated to contribute approximately 18% of global carbon dioxide equivalent emissions annually,1 and biochar is one of many promising solutions for addressing agricultural and land-use emissions.

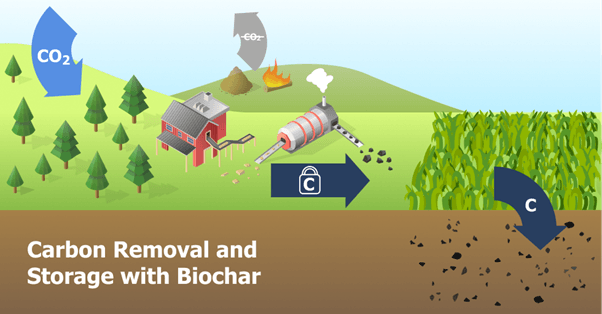

Biochar is a charcoal-like substance that is produced by heating biomass in a low-oxygen environment through a process called pyrolysis. The result is that carbon that has been captured through the life of the biomass is locked into the biochar. Typical biomass end uses such as burning or decomposition emit carbon, but by making biochar from the same material, this carbon is stabilised and is prevented from returning to the atmosphere.

In addition to being a stable store of carbon, when used as a soil amendment, biochar can provide numerous benefits to agricultural production, such as increasing soil quality as well as water and nutrient retention. It remains stable in the soil for thousands of years.

Source: Black Bull Biochar.

We got in touch with an innovative UK start-up in the area, Black Bull Biochar, to find out more.

The potential scope of biochar

Biochar has many applications, the primary one being to store carbon sequestered by biomass which would otherwise be re-released into the atmosphere. According to a study on the feasibility and costs of biochar deployment in the UK, biochar has the potential to sequester 3.6 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e) in a low-resource feedstock scenario using virgin biomass sources (derived from naturally occurring plants, where there is no chemical or biological transformation).2 This is the same amount of greenhouse gas emitted by over 800,000 gasoline cars in a year.3 In a high-resource scenario using both virgin and non-virgin biomass feedstocks, up to 21.9 million tCO2e could be sequestered.4

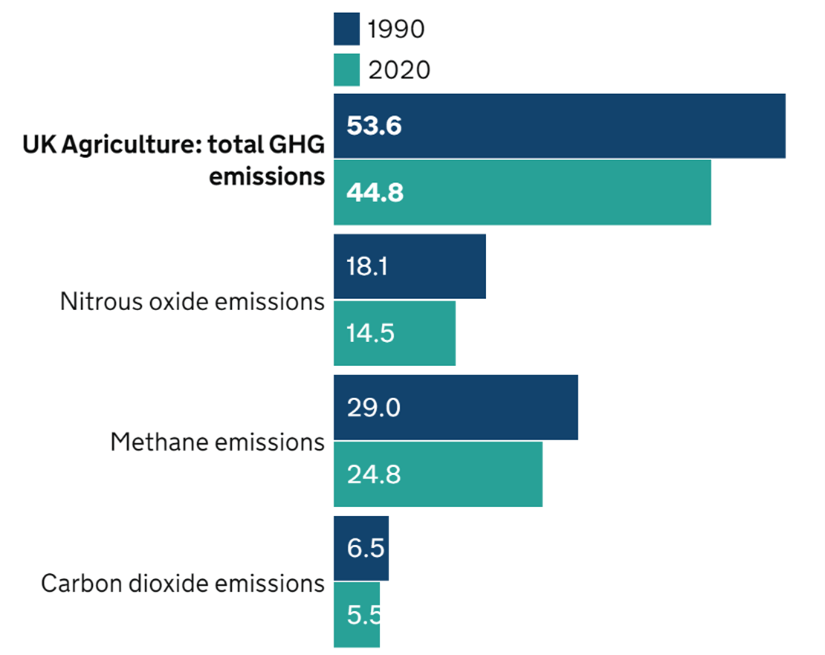

For context, in the UK, the total volume of emissions produced by agriculture in 2020 was estimated to be 44.8 million tCO2e.5 Biochar therefore has the potential to sequester equivalent to between 8% and 49% of UK agricultural-related emissions. It is not a panacea to agricultural and land-use emissions, but in a situation where every little helps, it could provide a worthwhile contribution.

The second key application of biochar is that when used as a soil amendment, the increase in soil water and nutrient retention can have a material impact on the amount of fertiliser required. 21% of UK agricultural emissions are nitrous oxide emissions from the use of fertilisers, the need for which can be reduced through the use of biochar.6

UK estimated greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions for agriculture, 1990 and 2020 (million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, MtCO2e)

Source: GOV.UK, Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs, 27 October 2022.

What are the challenges to expanding biochar use?

Availability of biomass

Biochar is highly versatile and can be made from a variety of feedstocks such as wood, food processing residues including rice husks and avocado pits, and even sewage sludge. What differs are the properties of the resulting biochar.7 While there is an abundance of biomass available, it is critical to select the right feedstock to produce biochar with the desired properties needed for its end use.

For example, by using sawmill co-products such as woodchip, Black Bull Biochar is producing a biochar product tailored for use in dairy farming.8 Over the long term, Black Bull Biochar aims to co-locate pyrolysis facilities with biomass sources, such as at sawmills and papermills. As such, it is currently focusing on developing biochar production in the North of England and Scotland, where most of these sites in the UK are concentrated.

Financing

Black Bull Biochar’s business model is built on three distinct revenue streams: income from economic renewable heat generated by pyrolysis units; revenue from high-quality, certified biochar, tailored to the use case of the customer; and sales of carbon removal credits.

The company sees a future in which suppliers and users of greenhouse gas removal (GGR) technologies are connected through a platform that enables biochar to scale. Once this system is established, the platform lays the foundation to bring together industry and agriculture into an international business-to-business GGR network that uses biochar to decarbonise our industrial and agricultural systems.

Demand from farmers

The key barriers to biochar adoption by farmers are a lack of awareness and high prices.9 Leveraging the revenue from high-quality carbon credits enables Black Bull Biochar to offer biochar to farmers at a lower price than they would be able to obtain elsewhere. Moreover, the company is working closely with pilot farmers in its demonstrator hub to develop best practices for using biochar on farms, and is creating resources to spread the word on how biochar works to benefit soil and animal health. By doing so, it is helping to create a market for biochar and is promoting sustainable agricultural practices that benefit both the environment and farmers.

The voluntary carbon market

Unlike most engineered carbon removal technologies, biochar production is a mature and well-established technology. Suppliers can produce biochar as soon as their pyrolysis equipment is set up. Since carbon removal occurs at pyrolysis, the associated carbon credits can be sold after they have gone through certification from accrediting bodies. To date, biochar has delivered 0.6 MtCO2e of carbon dioxide removal, which is over 90% of engineered carbon removals in the voluntary carbon market (i.e. carbon removals that have actually been delivered, rather than promised).10

Measuring sequestered carbon

Biochar is a carbon-rich material. The mass of carbon stored in biochar can be calculated by multiplying its dry weight by its percentage carbon content, which can be verified through laboratory analysis. Emissions from biochar production must also be accounted for to arrive at a net carbon removal contribution.11

Black Bull Biochar is developing a monitoring, reporting and verification process through its platform to track carbon from feedstock sourcing to biochar production, all the way through to biochar use on farm.

Legislation around the world

The European Union (EU) updated rules last year on permitted fertilising products to include biochar.12 In the US, the Biden administration has included biochar as a means of reducing agricultural nitrogen emissions in its ‘Bold Goals for U.S. Biotechnology and Biomanufacturing’.13 The UK is currently falling behind on legislation around biochar production and use. For now, biochar producers in the UK are looking to EU standards such as the European Biochar Certificate (EBC) as guidelines to adhere to.

Biochar remains fairly small scale at this stage, but it is important that, as investors, we research areas such as this given that we are talking to companies reliant on agricultural produce every day.

Sources:

- Our World in Data. Emissions by sector. Accessed 6 June 2023: https://ourworldindata.org/emissions-by-sector#agriculture-forestry-and-land-use-18-4

- Simon Shackley, Jim Hammond, John Gaunt & Rodrigo Ibarrola. The feasibility and costs of biochar deployment in the UK (Table 11). Carbon Management, 2:3, 335-356. 10 April 2014.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Greenhouse Gases Equivalencies Calculator – Calculations and References. 30 May 2023.

- Simon Shackley, Jim Hammond, John Gaunt & Rodrigo Ibarrola. The feasibility and costs of biochar deployment in the UK (Table 11). Carbon Management, 2:3, 335-356. 10 April 2014.

- GOV.UK. Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs. Agri-climate report 2022. 27 October 2022.

- Ibid.

- Ippolito, J.A., Cui, L., Kammann, C. et al. Feedstock choice, pyrolysis temperature and type influence biochar characteristics: a comprehensive meta-data analysis review. Biochar 2, 421–438 (2020).

- Alex Clarke, Hamish Creber, Dr Saran Sohi & Dr Jeanette Whitaker. Sofies. The Biochar Network – Demonstrating a Scalable GGR Solution. 14 December 2021.

- Market Data Forecast. Europe Biochar Market. Accessed 6 June 2023: https://www.marketdataforecast.com/market-reports/europe-biochar-market

- Cdr.fyi. Accessed 12 April 2023: https://www.cdr.fyi/

- Dominic Woolf et al. Greenhouse Gas Inventory Model for Biochar Additions to Soil. Environ Sci Technol. 12 October 2021.

- European Commission. Fertilising products – pyrolysis and gasification materials. Accessed 6 June 2023: https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/12136-Fertilising-products-pyrolysis-and-gasification-materials_en

- The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. Bold Goals for U.S. Biotechnology and Biomanufacturing. March 2023.

This is a financial promotion. These opinions should not be construed as investment or other advice and are subject to change. This material is for information purposes only. This material is for professional investors only. Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those securities, countries or sectors. Please note that holdings and positioning are subject to change without notice. Newton manages a variety of investment strategies. How ESG considerations are assessed or integrated into Newton’s strategies depends on the asset classes and/or the particular strategy involved. ESG may not be considered for each individual investment and, where ESG is considered, other attributes of an investment may outweigh ESG considerations when making investment decisions. ESG considerations do not form part of the research process for Newton's small cap and multi-asset solutions strategies.

Comments