In the latest economics, geopolitics and demographics themes group, we discussed the fiscal costs of ageing and how prepared various countries are to bear this burden.

While the world’s population is expected to increase from 7.5 billion today to 9.5 billion by 2050, the age composition is set to change as populations age rapidly, driven by a reduction in fertility rates and an increase in life expectancy.

The stats are stark. By 2050, it is estimated that 15% of the globe will be over 65, up from 8% in 2015. One key metric, the old-age dependency ratio (the share of over 65s as a percentage of the working-age population), is set to rise in most countries over the next 20 years (see chart below), with China and Western Europe expected to see the most marked increases.

Projected change in Old-Age Dependency Ratio from 2015 to 2035

Source: UN Population Information Network, 2015. For illustrative purposes only.

The Fiscal Costs of Ageing

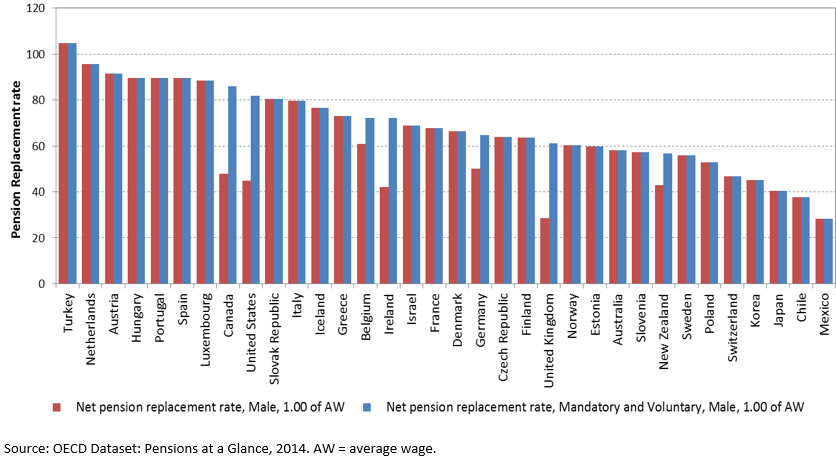

With ageing populations comes rapidly increasing numbers of retirees. The level of preparedness for this differs considerably between countries, but as a whole it appears governments, employers and individuals have not been putting enough aside to meet their future commitments. We can see this divergence between countries in their different expected net pension replacement rates (the proportion of after-tax pension received in retirement relative to after-tax earnings when working).

Source: OECD Dataset: Pensions at a Glance, 2014. AW = average wage. For illustrative purposes only.

With the state still dominating as a source of retirement income in many countries, governments are likely to come under increasing strain in future as these costs rise ahead of projected revenues.

The impending fiscal burden on states is considerable, and it’s not just pensions. Health care and long-term care for the aged are two other areas where government spending is forecast to increase substantially. In our view, Europe is particularly exposed to the consequences of changing demographics as countries typically run expensive ‘pay as you go’ state pensions. This means that pensions paid to today’s retirees are financed from contributions paid by current workers. So as pension costs increase, to remain in balance, the state has to take more from current workers or pay less to pensioners.

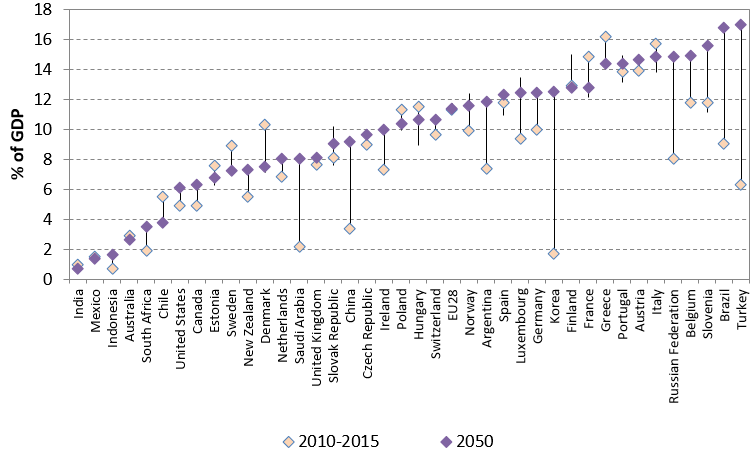

According to forecasts by the OECD, Germany, Ireland, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Slovenia all are forecast to see pension, health-care and long-term care costs rise by more than 4.5% of GDP per annum by 2050. In Austria, the Slovak Republic and Portugal costs are expected to increase by between 3% and 4% of GDP per annum.

Estimated Change in Government Pension Expenditure from 2015 to 2050

The few emerging economies for which data is available show some of the largest pension and health-care cost increases: by 2050, China and Russia are expected to see fiscal costs related to the above rise by over 8% of GDP, while Brazil, Turkey and South Korea are set to see theirs rise by well over 10% of GDP.[1]

In the case of the U.S., the U.S. Congressional Budgetary Office forecasts that social security and major health-care program spending is forecast to increase considerably – by 4% of GDP per annum or, as a percentage of government revenue, from 58% today to 76% by 2035 and 80% by 2047 – a clearly unsustainable trajectory.[2]

What Can Governments Do?

There are a few ways for governments to improve the outlook for future post-retirement incomes and reduce the pressure on the state pension system. The easiest option politically is to increase retirement ages as a number of European countries have done. This has frequently been combined with equalizing/narrowing the difference between the male and female retirement age, with the female retirement age rising more sharply as a result. This means people pay in for longer but also take less out of the system, which has made a meaningful improvement to the outlook for public pensions expenditure according to the most recent forecasts by the OECD. The increase in the retirement age pushes a disproportionate amount of the costs of retired/soon-to-retire workers onto younger workers. Nevertheless, this could be more palatable than cutting pension payouts.

Another option is to encourage or mandate enrolment into private pension plans to shore up private pension assets, which then reduces retirees’ reliance on state pensions in the decades to come. The UK government has been phasing this in from 2012 with its auto-enrolment initiative, with it now being compulsory for employers to automatically enroll their eligible workers into a qualifying workplace pension plan and contribute to the plan, unless employees explicitly opt out. Minimum contribution rates began at 2%, but will increase to 5% by October 2017 and will rise to 8% by October 2018 (5% contribution by companies and 3% by employees).

Despite undertaking some of these measures already, government pension expenditure is still set to rise in many countries.

Investment Implications

As pressure mounts on governments to support the growing elderly population, we believe it’s clear further reform will be necessary to keep pension systems and health-care programs affordable.

New significant sources of revenue are likely to be needed to fund the increasing number of retirees – this could come from a reduction in corporate profits via increased company contributions and/or a rise in taxes. It’s also likely in some cases that retirement benefits and other government services will need to be trimmed to make them more affordable, hopefully alongside increased private pension savings helping to support post-retirement incomes.

With governments facing huge pressure on their budgets, another consideration is the potential for a fall in discretionary spending if there is a reduction in state support for pensioners or a cut in public health services. After all, we’re not forecasting a wealthier population, just an older one.

For eurozone countries, the option for individual governments to depreciate their currency or print money to solve the debt problem is not available. Therefore, with the current institutional setup, it is possible some time in the future that a eurozone country facing a debt crisis (worsened by rising age-related expenditure), and which is unwilling to embrace the necessary reforms placed on it by the rest of the euro group in return for a bailout, may instead choose to leave the single currency.

[1] Source: OECD (2017), “Pensions at a glance”, OECD pensions statistics database; OECD (2016) Healthcare at a Glance: Europe 2016; OECD (2013), Public Spending on health and long-term care: a new set of projections.

[2] Source: U.S. Social Security Authority, U.S. Congressional Budgetary Office, 2017.

This is a financial promotion. Material in this publication is for general information only. The opinions expressed in this document are those of Newton and should not be construed as investment advice or recommendations for any purchase or sale of any specific security or commodity. Certain information contained herein is based on outside sources believed to be reliable, but its accuracy is not guaranteed. You should consult your advisor to determine whether any particular investment strategy is appropriate. This material is for institutional investors only. Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell this security, country or sector. Please note that strategy holdings and positioning are subject to change without notice. Compared to more established economies, the value of investments in emerging markets may be subject to greater volatility, owing to differences in generally accepted accounting principles or from economic, political instability or less developed market practices.

Important information

This is a financial promotion. Issued by Newton Investment Management Limited, The Bank of New York Mellon Centre, 160 Queen Victoria Street, London, EC4V 4LA. Newton Investment Management Limited is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority, 12 Endeavour Square, London, E20 1JN and is a subsidiary of The Bank of New York Mellon Corporation. 'Newton' and/or 'Newton Investment Management' brand refers to Newton Investment Management Limited. Newton is registered in England No. 01371973. VAT registration number GB: 577 7181 95. Newton is registered with the SEC as an investment adviser under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. Newton's investment business is described in Form ADV, Part 1 and 2, which can be obtained from the SEC.gov website or obtained upon request. Material in this publication is for general information only. The opinions expressed in this document are those of Newton and should not be construed as investment advice or recommendations for any purchase or sale of any specific security or commodity. Certain information contained herein is based on outside sources believed to be reliable, but its accuracy is not guaranteed. You should consult your advisor to determine whether any particular investment strategy is appropriate. This material is for institutional investors only.

Personnel of certain of our BNY Mellon affiliates may act as: (i) registered representatives of BNY Mellon Securities Corporation (in its capacity as a registered broker-dealer) to offer securities, (ii) officers of the Bank of New York Mellon (a New York chartered bank) to offer bank-maintained collective investment funds, and (iii) Associated Persons of BNY Mellon Securities Corporation (in its capacity as a registered investment adviser) to offer separately managed accounts managed by BNY Mellon Investment Management firms, including Newton and (iv) representatives of Newton Americas, a Division of BNY Mellon Securities Corporation, U.S. Distributor of Newton Investment Management Limited.

Unless you are notified to the contrary, the products and services mentioned are not insured by the FDIC (or by any governmental entity) and are not guaranteed by or obligations of The Bank of New York or any of its affiliates. The Bank of New York assumes no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the above data and disclaims all expressed or implied warranties in connection therewith. © 2020 The Bank of New York Company, Inc. All rights reserved.