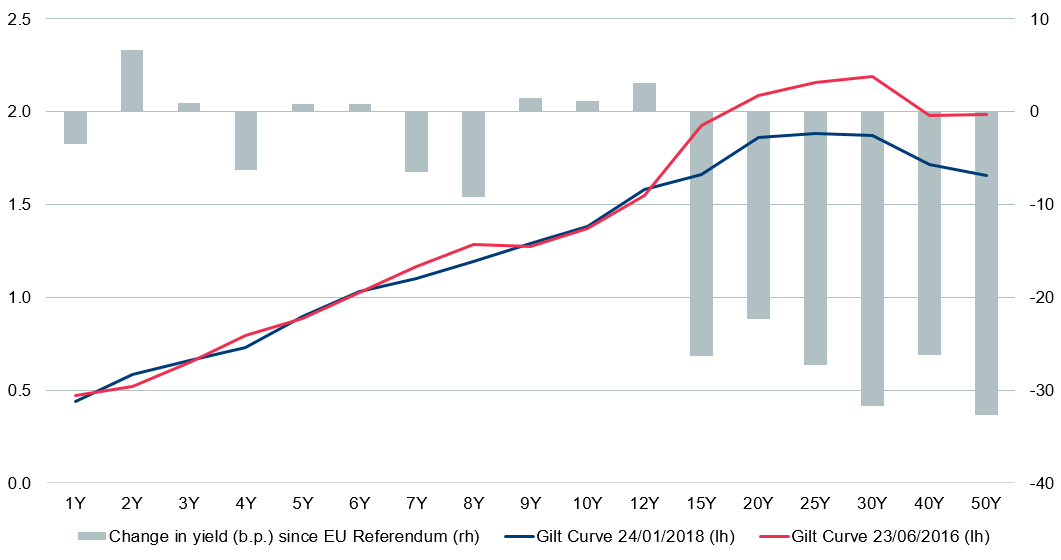

The chart below shows the shape of the UK gilt curve now (blue line), and on the date of the UK’s European Union (EU) referendum, 23 June 2016 (orange line). It also shows the change (in basis points) in yield between the two dates (grey bars).

It is noteworthy that UK gilt yields between one and twelve years to maturity are essentially the same now as on the day of the referendum (when the assumption in financial markets was that the UK would be voting to remain in the EU), but long-dated yields are about 0.3% lower now than they were then.

Change in UK gilt yields since the EU referendum (basis points)

Source: Bloomberg, 24/1/17

Long-dated drop-off

To some extent, one can rationalise the unchanged level of the short-to-medium end of the curve on the basis that the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee announced a further £70 billion of quantitative easing and made an emergency rate cut in August 2016, before reversing it in November 2017. Also, in June 2016, as now, expectations were that further modest and gradual rate increases would follow, which explains the same gently upward-sloping curves.

However, the long-end yield drop in particular looks very anomalous when one considers that the main impact of the referendum to date has been on inflation, via sterling depreciation. In June 2016, the consumer prices index stood at 0.5%, and currently it is at 3.0%, meaning that real yields on gilts are much more negative than they were. This is more evident in the index-linked gilt market, where real yields are between 0.5% and 0.75% lower than they were in June 2016.

Although inflation looks set to decline, it is not forecast to fall to the Bank of England’s 2% target for nearly two years.

Two possible justifications for lower long-dated gilt yields, inflation notwithstanding, are:

- Prospectively lower economic growth over the medium term once the UK leaves the EU, which would increase the relative attractiveness of gilts versus traditionally riskier assets. Although that may be the consensus view in the City, others would argue that the UK can prosper without being tied too closely to a structurally challenged EU.

- Actuarial demand. As equity markets have risen and bond yields have also nudged off their lows, defined benefit (DB) pension scheme funding ratios have improved, making it more affordable (and palatable) to reduce funding risk in schemes by increasing the allocation to bonds. The most recent Pension Protection Fund data shows the average DB scheme is 94.7% funded, much improved from the position in August 2016 (76.1%), when the worst actuarial effects of the referendum results (lower equities and slumping bond yields) were being felt.

However, other arguments against gilts relate to fundamentals and technicals:

- Fundamentally, forecasts for UK debt/GDP are materially worse than they were prior to the referendum. In March 2016 (the last forecasts published before the referendum), the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) was forecasting debt/GDP for fiscal year 2020/21 of 74.7%. Its latest forecasts, coinciding with last November’s Budget, now estimate the ratio will be 83.1%. That is not to say that the deterioration is all down to Brexit – the lack of productivity growth is another salient contributor.

- From a technical perspective, higher debt ratios (whatever their cause) translate into higher borrowing, and hence greater supply of gilts. Using the same OBR forecasts, back in 2016, public sector net debt was expected to reach £1.74 trillion by April 2021. That has now been revised up to £1.88 trillion. Most of this extra £0.14 trillion of borrowing translates into extra gilt issuance, although the Bank of England has already mopped up £60 billion (or 43%) of this ‘unexpected’ gilt supply through its post-referendum quantitative easing expansion in late 2016/early 2017.

Politics also seems to offer more threats than opportunities for gilt investors:

- We have already seen a small amount of fiscal loosening, but with pressures building in the NHS, and calls for higher defence and security spending and higher public-sector pay, the current government may feel compelled to go further to arrest its slide in the opinion polls.

- Furthermore, the current government is very fragile (split over Brexit, and propped up by Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party), and there is a non-negligible risk of an election before 2022. Labour, the main opposition party, and leader in the polls, has much more ambitious plans to increase public spending and renationalise certain industries.

- In terms of Brexit, any signs of a smooth transition period and a close (frictionless) continuing relationship with the EU would be likely to prompt a recovery in confidence and investment, bringing forward the timing of future interest-rate increases. While a hard, ‘cliff-edge’ Brexit may have the opposite effect, it could also deter overseas buyers of gilts, on whom the UK is highly dependent to fund its deficit.

For these reasons, we think an outright short gilts position (being short gilt futures) is appropriate in an absolute-return bond strategy, and that a significantly underweight/shorter duration stance is called for in gilt-benchmarked funds.

This is a financial promotion. Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those countries or sectors. Please note that holdings and positioning are subject to change without notice.

Comments