Nothing sets a central banker’s nerves on edge like deflation. The received wisdom within the halls of inflation-targeting central banks is that consumer price index (CPI) deflation – declines in the prices of goods and services – is anathema to a sustainable and strong economic expansion. The threat of deflation in the wake of the financial crisis was one of the reasons central banks initiated what has become nine years of hoovering up trillions of dollars’ worth of financial assets.

The almost reflexive association of deflation with economic weakness is easily explained by turning to the framework that has come to dominate central banking.

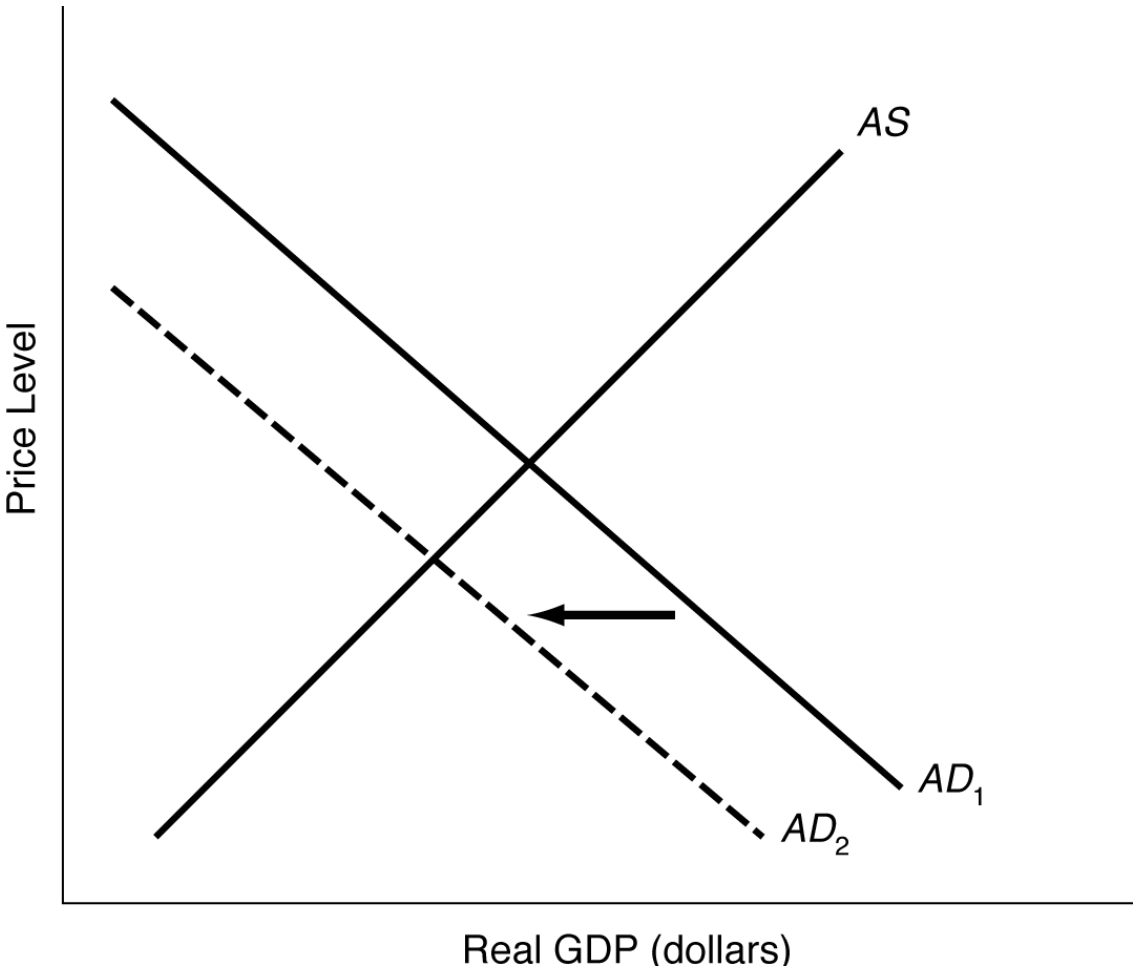

For illustrative purposes only

Source: Newton

It is rooted in the view that CPI deflation signals a deficiency of aggregate demand (represented by a shift of the demand curve from AD1 to AD2 in the above chart). A decline in aggregate demand sees output decline to a lower equilibrium level of output (real GDP). With GDP statistics infrequent and often difficult to measure, central banks use changes in CPI to infer what is going on with underlying demand; falling prices equate to soggy demand.

The need to ‘juice’ CPI inflation is also informed by concerns that high levels of global debt leave economies vulnerable to a ‘debt deflation’ dynamic taking hold if currently low levels of CPI inflation cross the Rubicon into deflation. US economist Irving Fisher famously argued that deflation increases the real cost of debt, which in turn lessens the ability of debtors to spend, thus reducing economic activity and increasing the risk of default.[1] Given the distribution of debt at the time, Fisher’s concerns focused on businesses; in the post-crisis world, policymakers harbour the same concerns for households and governments. But are central bankers and economists right to fear CPI deflation, and is the supposed link between economic growth and CPI fact or fiction?

Good deflation

As I discussed in ‘Throwing a curve ball’, falling prices are the natural outcome of a capitalist system where the forces of creative destruction drive improvements in productivity and increases in supply. Such supply-driven deflations go hand in hand with rising output and incomes – the opposite outcome to CPI declines, which are brought about by supposed deficiencies of demand.

Empirical analysis by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS),[2] looking at over 140 years of data (which importantly includes a wide range of monetary regimes from up to 38 countries), confirms that the link between changes in CPI and output growth is weak and episodic at best. In the classical Gold Standard era (1870-1914), growth in output was found to be marginally lower after CPI peaked. In the post-World War II era, growth in output per capita has actually been higher following a peak in CPI prices. So where does the central-banker obsession with the perils of CPI deflation stem from?

The Great Deception?

I would argue the obsession stems from an incorrect analysis of the Great Depression, when falling prices did indeed accompany a severe global economic contraction. The BIS authors found that, during the inter-war period when the Great Depression took place, growth in output per capita was negative following the peak in CPI. So does this vindicate the conclusion that price deflations lead to lower, or even contractions in, economic output, or is this a case of correlation masquerading as causation?

In the same paper, the authors analysed whether asset-price deflations had any impact on output growth. They found a strong positive and statistically significant correlation between output growth and asset prices (equity and property). Declines in asset prices, not goods and services, have negative consequences for output growth.

Furthermore, and of particular importance, once persistent asset-price deflations are controlled for, goods and services (CPI) deflations do not appear to be linked in a statistically significant way with slower growth, even in the inter-war period. That is to say that the contraction of output during the inter-war period was not the result of falling goods and services prices, but the result of falling asset prices.

Fishing?

This view invites scepticism of Fisher’s theory of ‘debt deflation’. To assess whether the theory has any merit, the BIS authors tested whether the cost of deflation in terms of output growth (if indeed there is one), is related to debt, both in terms of the absolute level and the increase in leverage (debt to GDP) prior to the peak in prices.

They found no evidence that high debt or a period of excessive debt growth led to CPI deflations having a cost in terms of economic growth. They did, however, find that high levels of debt and increases in leverage increased the cost in terms of output growth in the period following a peak in asset prices.

This finding makes perfect sense if we consider the interplay between debt and asset prices. Declines in asset prices impair balance sheets and increase financial stress; the more leveraged a balance sheet is, the greater the financial stress and the greater the economic cost.

Conclusion

This analysis is a serious challenge to the prevailing view in central banking that falling goods and services prices are always pernicious. As I have shown, CPI tells us nothing about what is happening to economic output or incomes. As such, even for those who want to ‘manage the economy’, there is little case for using CPI statistics to guide monetary policy.

Furthermore, it is misleading to draw conclusions about the cost of deflation in terms of output growth from the experience of the Great Depression. The episode was an outlier in terms of output losses following the onset of CPI deflation. In addition, it is highly likely that the scale of those losses had little to do with the fall in the price level. Rather, it was asset-price declines and the ensuing financial stress that led to the Great Depression – stress that had been building outside of the US long before the 1929 crash.

Second, inflation tells us very little about broader credit inflations – the inflation that matters with respect to financial and economic stability, which I covered earlier this year.

As the above analysis shows, asset-price deflations come at a significant cost to economic growth. As policymakers look set to remove the liquidity that has levitated asset prices so successfully, it is not just asset prices that are at risk.

[1] The concept of ‘debt deflation’ was first outlined by US economist Irving Fisher in 1933, as an attempt to explain the Great Depression.

[2] The costs of deflations: a historical perspective >http://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt1503e.pdf

Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those countries or sectors. Please note that holdings and positioning are subject to change without notice.

Comments