When looking at the performance of the government bond markets, one can’t help thinking of Wile E. Coyote, the hapless antagonist of the Road Runner cartoons. He runs at full speed along narrow clifftops, his momentum carrying him some way beyond the cliff’s edge, before plummeting dramatically downwards.

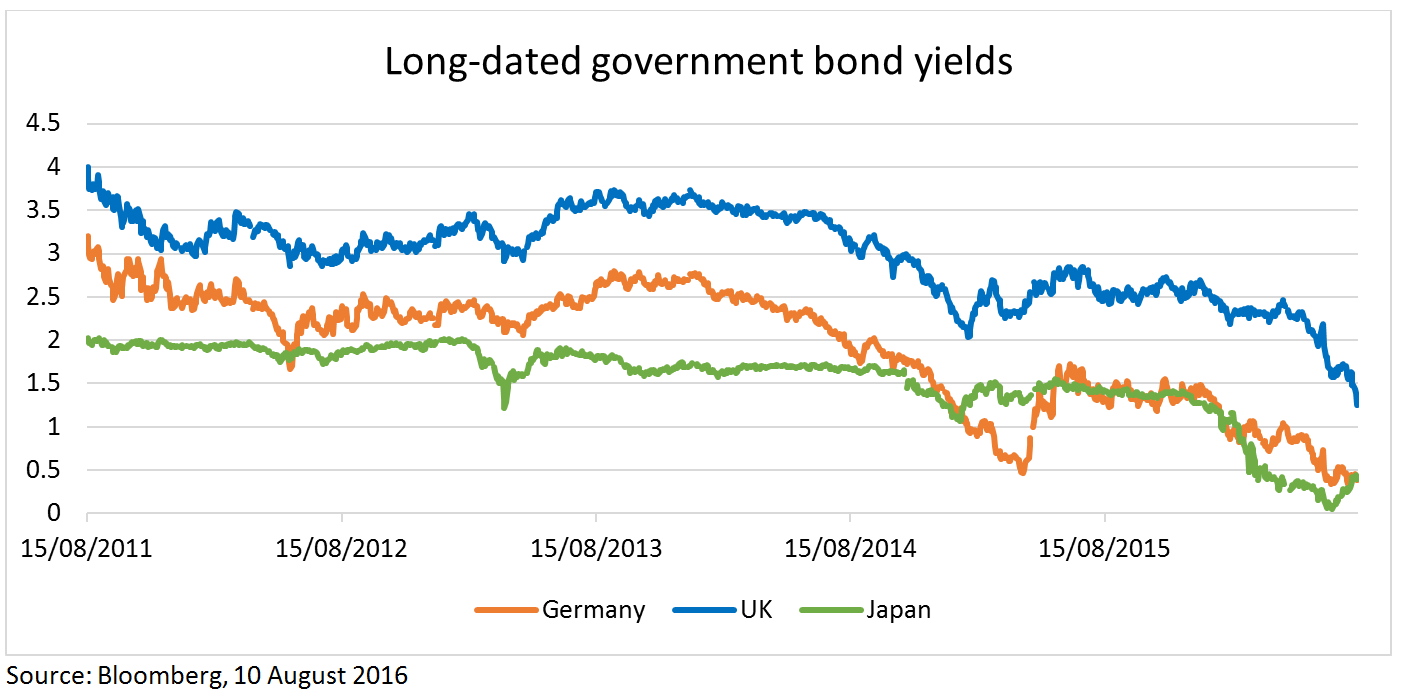

The 30-year gilt has been on a tear over the last year, providing a total return of +33.8% (source Bloomberg, year to 15 August 2016), and its performance accelerated upwards (with yields falling correspondingly) after the UK’s vote to leave the European Union in June.

As you can see from the chart below, the UK market is on its way to joining the German and Japanese bond markets with extremely low levels of yields.

The driving force of these moves is of course the move towards zero cash interest rates, combined with central bank bond purchases. Without an increase in supply, the new demand (from the central banks) naturally lowers the yield and raises the price until the point when other investors are happy to let the bonds go. The market moves so far are understandable given these extraordinary monetary policies, but what if these policies change?

Fiscal therapy

To us, there seems to be a growing recognition that monetary policy cannot continue on its own and that fiscal stimulus may also be required. Could this be the death knell of the 35-year bull market in government bonds? Could government bond markets find themselves running in mid-air and meet the fate of Wile E. Coyote?

To us, there seems to be a growing recognition that monetary policy cannot continue on its own and that fiscal stimulus may also be required. Could this be the death knell of the 35-year bull market in government bonds? Could government bond markets find themselves running in mid-air and meet the fate of Wile E. Coyote?

For this to happen you need a wave of sellers to offset the demand from central bankers and those being squeezed up the curve. The fear of losing capital is not sufficient for a sustained bear market in bonds to begin. The most likely catalyst for sellers of bonds to appear is the belief that there is an alternative; there needs to be somewhere else to put the money. Alternative asset classes such as gold and property are not liquid enough to be serious candidates for the shift in allocation – we need to look to the equity markets before we can get a real move.

Fiscal stimulus that creates an improved economic outlook and perhaps causes pockets of inflation is good news for equities but very bad news for ‘Wile E. Coyote’-like bond markets.

Continuing momentum

Bringing an end to the bond run and turning bearish on bond markets that are inflated by central bank activity and a prolonged deflationary backdrop are not things that happen quickly. There won’t be a wholesale adoption of fiscal policies that will successfully turn economies around and lead to a renewed investment programme from cash-rich companies. Many investors have been burnt by getting out too early from bond markets that don’t ‘offer value’. Being short the Japanese government bond market has been a painful experience for those that have tried it.

The message we have delivered since the global financial crisis is that any ‘safe-haven’ bond that has a higher rate than cash should offer ‘value’ while the deflationary backdrop of restructuring the banking system remains in place. This part of the story hasn’t changed – in fact it is what gives old Wile his momentum – but as we can see in the US, if the banking system has been restructured there is a resistance to lower yields.

There is genuine scepticism that, after such a prolonged period of below-trend growth, a move back to ‘normal growth’ is possible. After all, the central bankers have thrown the kitchen sink at the problem and yet nothing has changed. This argument is valid, but the lower yields go the greater the fallout if (and only if) the authorities are able to create inflation, and the lower the upside if they cannot.

Staying on firm ground

Therefore, even if it is not possible to say whether fiscal stimulus will work, in our view it seems prudent to adjust bond positioning beforehand.

Across our fixed-income strategies, we have reduced exposure to those markets where central bank activity has almost run its course and fiscal policy is about to be loosened. Fortunately, these are some of the most expensive (and low-yielding) bond markets around. Owning bonds in markets where monetary policy could still be eased further seems logical (Australia, US). Also, owning inflation-linked bonds where markets are not fully pricing in the central bank’s ability to match their targets could also be a good way of balancing risks.

Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell this security, country or sector. Please note that holdings and positioning are subject to change without notice.

Comments