The recent back-up in interest rates has been interpreted by many as a vote of confidence in the health of the US economic outlook, but we’re not so sure.

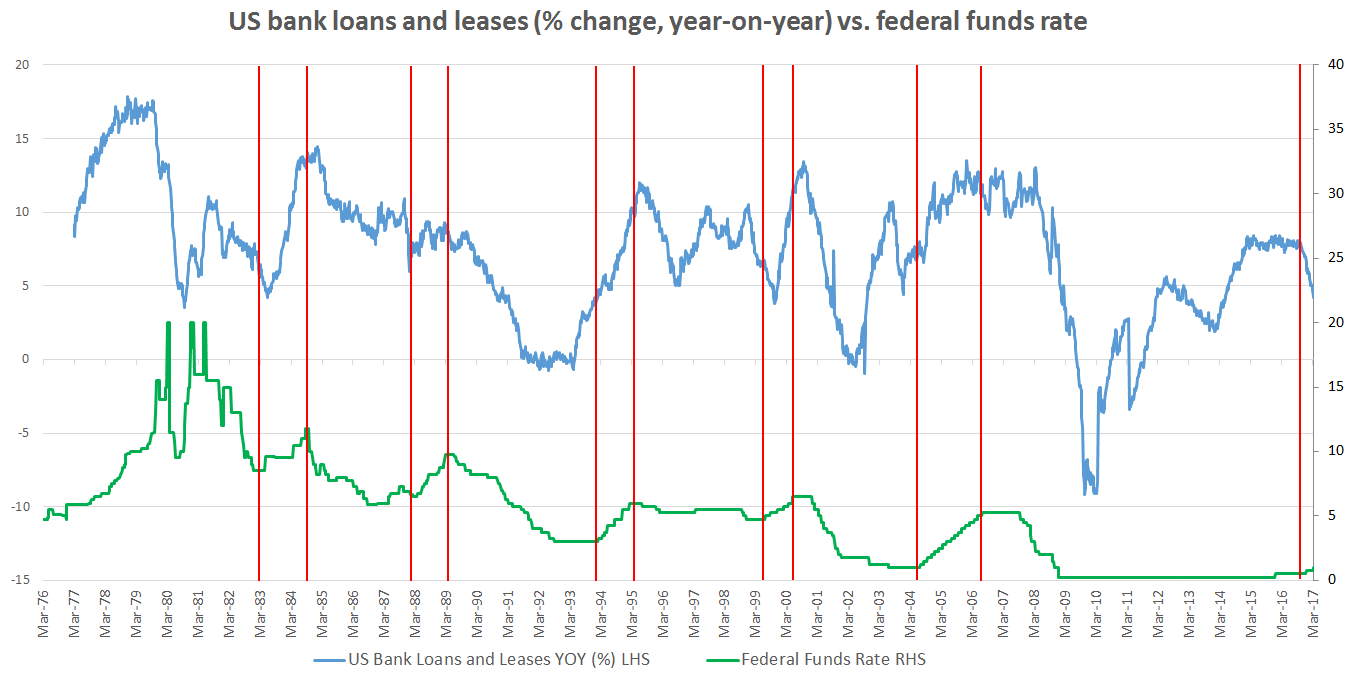

Historically, Federal Reserve (Fed) rate-hiking cycles have gone hand-in-hand with an advance of the equity market. However, where the current ‘rate-hiking cycle’ differs from those of yesteryear is in the slowdown of bank loan growth.

Since 1980, whenever the Fed has been hiking interest rates, US commercial bank loan growth has been accelerating. The blue line in the chart below shows year-on-year loan growth (on the left-hand scale), while the green line shows the federal funds rate (on the right-hand scale). In effect, the economy has been able historically to afford higher interest rates.

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream, April 2017

Since interest rates rose in the wake of the US election, US commercial bank loan growth has slowed rapidly. This slowdown in response to higher bond yields suggests that the real economy is struggling to pay higher rates.

Last year, the US managed only 20.6 cents of nominal GDP growth for each additional dollar of debt; that means that 79.4 cents went towards servicing existing debt. With economic growth so debt-dependent (as opposed to the type of productivity growth central to the process of creative destruction[1]), the slowdown in credit growth is highly likely to lead to a slowdown in economic growth.

This means earnings growth is unlikely to accelerate to justify now even loftier multiples, unless there is a sudden (unanticipated) productivity boom. Ironically, the rally in the equity market since the election has deprived the real economy of the liquidity required to make debt finance affordable, given that the liquidity which fuelled the equity-market advance appears to have been sourced from the bond market rather than via an expansion of US broad money. Unless the US corporate sector takes advantage of cheaper equity finance to fund a substantial increase in capital expenditure, this makes earnings growth even less probable.

[1] A term coined by Joseph Schumpeter in 1942 to describe the “process of industrial mutation that incessantly revolutionises the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one”.

Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those countries or sectors.

Comments