Significant changes occur when there is a shift in the balance of power between the world’s major blocs. With China poised to take the role of top global economy from the US, I’ve been thinking about the comparison with what happened when the UK surrendered that title to the US between the two world wars.

Historically, we have seen that, as the old guard loses its leadership in economic and political terms, the successor is initially reluctant to take on the political mantle, despite being very willing to take on the economic one.

At its inception, the US wanted to focus on its own priorities – chiefly exploiting its own abundant natural resources of commodities and a young and growing workforce. Only when its economy started to outgrow these did it pay attention to the rest of the world.

The same can be said about modern-day China, which has ignored conflicts in the Middle East and looked elsewhere for investment opportunities.

The slow death of one superpower can depress the world economic system, but the birth of another can keep it alive as resources are switched from one to the other. However, the growth of the new economy, as it transforms from minor player to top nation, inevitably goes through fits and starts, and booms and busts. Transforming workforces and building a first-world nation requires large amounts of capital (and therefore borrowing). There is the occasional credit blow-up as a result; we can see this happening in China now.

When a bubble bursts, but the new economy can recover while the rest struggle, it has achieved ‘top-dog’ status. The US stock-market crash of 1929, for example, sent the world into a tailspin from which it took decades to recover, but it was the US that ultimately came out on top.

Timeline

This is a timeline of what happened with the UK/US change, and where we are now with the US/China handover. As you can see, it suggests we are only part way through the latter

The beginning of the end

As a starting point, we can take 1914 as the peak of British influence. There was worldwide peace and stability, and little domestic trouble, while trade and globalisation were high and Britain’s power and morale were unchallenged.

In the US, the federal government was planning to introduce income tax, and banks were grumbling about the proposed creation of the Federal Reserve (the Fed). US focus was close to home, for example on revolution in Mexico.

By 1918 in the UK, there was significant post-war debt, the population was devastated, and there was massive internal dissent. Within a few years, the empire started splitting up.

The 1920s are sometimes referred to as the ‘Roaring Twenties’, but for the UK economy they were a period of depression, deflation and a steady decline in economic pre-eminence. In the US, the economy boomed on the back of mass production techniques, growing efficiency – and increasingly a credit bubble, which would later contribute to the stock-market crash and great depression.

The inflection point: 1929

The 1907 US stock-market crash, when the market dropped 50% from its peak, had less influence on the world than the 1929 crash. History tells us that the latter came on 24 October 1929, but nothing as complex as the Great Depression happens in a single stroke. As early as the spring of 1927, the Bank of England lowered rates to boost the UK economy, and, in response to the resultant capital flight (from the UK to the US), forced the Fed to lower rates – which led to an inflationary cycle and an orgy of stock speculation. The Dow rose 250% in two years.

The shift from monetary to political influence

The central banks of the UK, Germany and France were joined by the US, with the creation of the Fed in 1914. There followed a period of rising political tension, with centrists losing ground to extremists.

On the international stage, the US moved from isolationist policies (which had dominated international relations since Washington’s presidency in the late 18th century) to being world leader by the end of the Second World War (WWII).

After discarding the non-interventionist approach temporarily in 1917 by declaring war on Germany, the US returned to isolation and rejection of the League of Nations. WWII later split Americans into two camps, but ultimately Pearl Harbor tipped the balance. The effects of two world wars on the European economy left the US as the dominant economic power after WWII, and pent-up consumer demand, leaps in technology, and firm support from the infrastructure plans after the Great Depression led US GDP to grow much faster than UK GDP. The US was in the position to dominate the policies of rebuilding the defeated nations through structures such as the Marshall Plan, given its better capital position. It also took charge of rebuilding international cooperation by creating the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

The NEW beginning of the end

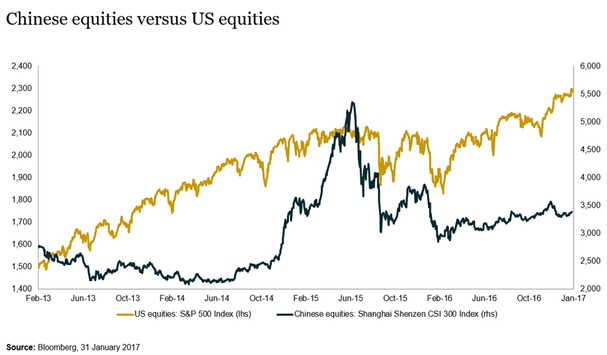

Clearly, for markets, the US is still the dominant player, as the events of 2008 highlighted. And, as the chart below shows, the bubble in Chinese stocks over the 12 months to mid-2015, and subsequent collapse over the nine months thereafter, had very little impact on other markets.

We are yet to see an event similar to the 1929 US stock-market crash hit world markets, but few who have looked at the rise in Chinese credit are complacent. The next bursting of the Chinese bubble could cause significant problems globally, given the relative shortage of tools available to central bankers to tackle problems.

The NEXT inflection point – 2018?

The 2008 credit crisis had little to do with China in its origin, but Chinese authorities stimulated their economy in any event. The effect on the domestic economy was less pronounced than in previous cycles, and much of the fresh money has gone into asset-price speculation. Given high levels of developed-market debt and low interest rates, one could argue that China might be able to respond better than the West to the next economic shock that its economy causes. Countries with low government debt-to-GDP levels and currency reserves might also find it easier to survive.

The shift from monetary to political influence

2016 was a year when political shocks took pre-eminence, after a prolonged period when central banks were the main drivers of asset returns. Brexit, Trump and the Italian rejection of a referendum on constitutional reform pointed to growing dissatisfaction with the status quo.

In 2017, things are set to be even more interesting, with key elections in Germany, France and the Netherlands. Meanwhile, the new US administration is planning to change fiscal policy quite dramatically. This is highly likely to start a trade war, which would significantly affect the countries that have built their economies on the back of trade with the West. China stands to lose the most.

Conclusion

There are many similarities between Acts 1 and 2 above, but also many differences, including speed of communication, the timing of economic versus political control, and the role of floating rather than fixed currencies. However, one thing is clear: as in 1929, the next crash of the new nation (in today’s case China) is likely to leave a significant dent in the global economy.

Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those countries or sectors. Compared to more established economies, the value of investments in emerging markets may be subject to greater volatility due to differences in generally accepted accounting principles or from economic, political instability or less developed market practices.

Comments