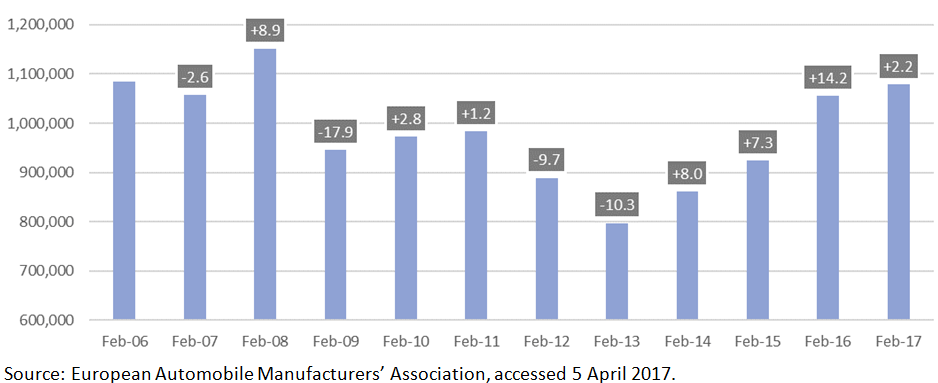

Auto sales have been on a tear of late. According to data from the European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association, new passenger car registrations in the European Union rose over 12% year-on-year in the first two months of 2017. In the UK, the story is similar. The Society of Motor Manufacturers & Traders (SMMT) says the number of new cars registered in March rose more than 8% against the previous year.

Figure 1: New passenger car registrations in the EU – monthly trend, 2007-2017

At first sight, this seems like great news for manufacturers and their associated sales, financing and distributions networks – but all may not be what it seems.

Looking under the bonnet…

First, many of these new sales are predicated on the availability of cheap credit. In the UK this takes the form of personal contract plans or PCPs, a form of hire purchase where the driver pays an initial deposit in addition to regular monthly payments, generally over three to four years. At the end of the term, the buyer can then hand over a final ‘balloon’ payment to own the car outright – or trade in the car for a new model and a new monthly payment plan.

For consumers, the arrangement reduces the upfront cost of owning a new vehicle, while carmakers can take advantage of those smaller upfront costs to tempt buyers with higher-margin purchases. One consequence has been a boom in sales of sport utility vehicles, which have risen by more than 20% a year in the UK since 2010.[1]

Figures from the Finance & Leasing Association show how successful PCP financing has been. In 2016 alone, it says, UK households borrowed a record £31.6bn to buy cars, a 12% increase on the previous year. Close to nine out of ten private car buyers are now using PCPs to fund their purchases.[2]

But now it seems the cheap auto finance trade could be coming to the end of the road – at least if recent data from the US is to be believed.

Used vehicle prices and sub-prime car finance: the canary in the cage?

One factor is falling prices for used vehicles as the supply of cars coming back to market after expired buy-and-lease agreements begins to climb.[3] This matters because it means lower trade-in values for customers coming to the end of those three- or four-year finance deals. In turn, that means lower deposits for new replacement vehicles and so weaker sales and higher inventories for dealers.

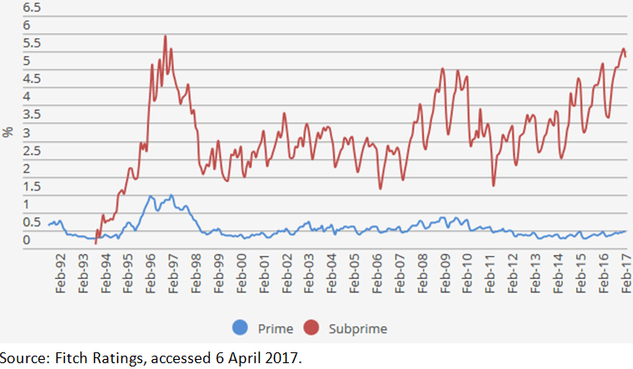

Figure 2: 60-day delinquency rate for US auto loans

At the same time, and against a backdrop of rising US interest rates, the number of defaults on sub-prime car loans has begun to rise. In March, ratings agency Standard & Poor’s highlighted how losses on US sub-prime auto loans reached an annualised 9.1% in January from 8.5% in December, and from 7.9% in the first month of 2016. The rate is the worst since January 2010, and is largely driven by worsening recoveries after borrowers default, according to S&P.[4] Morgan Stanley data paints a similar picture: it notes how a quarter of the more than US$1.1 trillion in US auto loan debt is owed by sub-prime borrowers, adding that delinquency rates have hit their highest point in seven years. [5]

The bigger picture

To us, the looming crisis in car finance is part of a wider malaise. Following the global financial crisis, governments, companies and consumers all took on more and more debt with little regard for the long-term consequences. The recent Trump-fuelled stock market rally was based partly on a belief that deregulation of the financial services sector would free up banks and other lenders to lend more – and that this in turn would result in a spending boom.

In theory, it’s fantastic. Except for two things: first, corporate and consumer debt are at all-time highs. This idea that there is huge pent-up demand for additional debt may be a bit optimistic. We would argue – as evidenced by recent delinquency rates in auto financing – that many people have already got as much debt as they can handle. Secondly, given those elevated levels of debt, we think it would only take a small increase in the interest rate for people to begin struggle to service their payments. This is already beginning to happen, and looking further down the road we believe it could begin to be a real problem. Admittedly, the scale of lending on auto loans is far lower than mortgage loans during the financial crisis – but we still think the idea that things are beginning to normalise is quite far-fetched.

[1] Source: HIS market data; FT: ‘Are the wheels about to fall off car finance?’, 24 March 2017

[2] The Finance & Leasing Association, 10 February 2017

[3] Data compiled by the US National Automotive Dealers Association showed a 3.8% decline in resale values for February compared to the previous month.

[4] Bloomberg: ‘U.S. Subprime Auto Loan Losses Reach Highest Level Since the Financial Crisis’, 10 March 2017

[5] Bloomberg: ‘“Deep Subprime” Auto Loans Are Surging’, 28 March 2017

Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those countries or sectors.

Comments