Recent political events across much of the developed world have signalled an end to the policy consensus that has existed for most of the last 30 years. The free-market liberalism which took hold in the US and UK in the early 1980s, and subsequently across much of the developed and emerging world, heralded a period of economic stability and globalisation, which has been characterised by the free movement of capital, labour and trade.

Globalisation has, in aggregate, led to economic gains, and has created many winners. A wide range of developing economies have benefitted from increased trade, with countries such as China exporting cheaper goods to the West, resulting in millions being lifted out of poverty and the emergence of a growing middle class. Consumers in developed markets have also gained from cheaper, imported products and from increased choice and competition.

However, there have been losers too. Most notably, many jobs in developed economies have been lost and transferred to lower-cost countries. In other cases, middle-class workers have seen their pay stagnate for years, often with the perceived threat of jobs being exported to the developing world. Workers have also faced the challenge of technological disruption, with many traditional jobs at risk in sectors such as retail as businesses move online. Such an environment has led to wage deflation: taking the UK as an example, the chart below highlights that while the country’s GDP has risen over the last 20 years, wages have fallen in real terms, with average wages lower than they were 20 years ago.

UK wages as percentage of GDP vs nominal GDP

In the US, while unemployment may be at its lowest rate for 50 years, the low-paid nature of numerous positions means that many individuals are struggling to make ends meet. According to the US Census Bureau, over 50% of under-18s live in a household receiving welfare payments.[1] This is reflected by data which shows that the US corporate sector’s share of gross value added (measured by after-tax profits) has risen to record highs over the last 20 years, while employee compensation’s share has significantly declined.[2]

The crisis effect

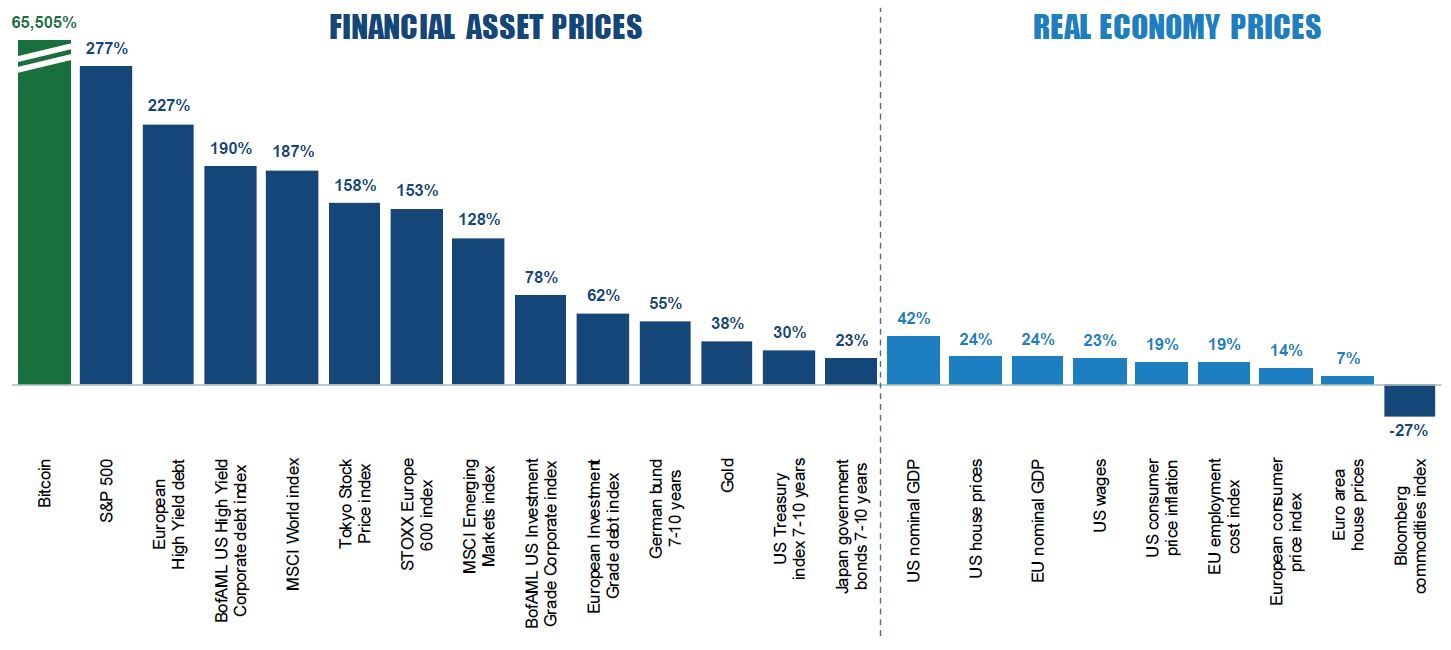

The aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis has reinforced the trends which had already been developing over the previous two decades. Extraordinarily loose monetary policy such as quantitative easing has driven asset prices higher. However, this price inflation has been concentrated in financial assets, and so those people with assets have seen their wealth inflated, while those without such assets have seen them become often unaffordable. With the great bulk of financial assets owned by the few (a study suggests that 84% of US stock-market wealth is owned by 10% of the population[3]), the result has been an increase in inequality.

Total return performance in local currency since January 2009

In addition, while profits have soared once again, wages have stayed low and public services have been cut, while governments have made little headway in tackling the effects of longer-term structural challenges facing their economies, such as the debt mountain, ageing demographics, and technological disruption. With austerity a near-permanent feature in recent years for many countries, it is perhaps unsurprising that more extreme politics have begun to attract growing support.

The inexorable rise in populism

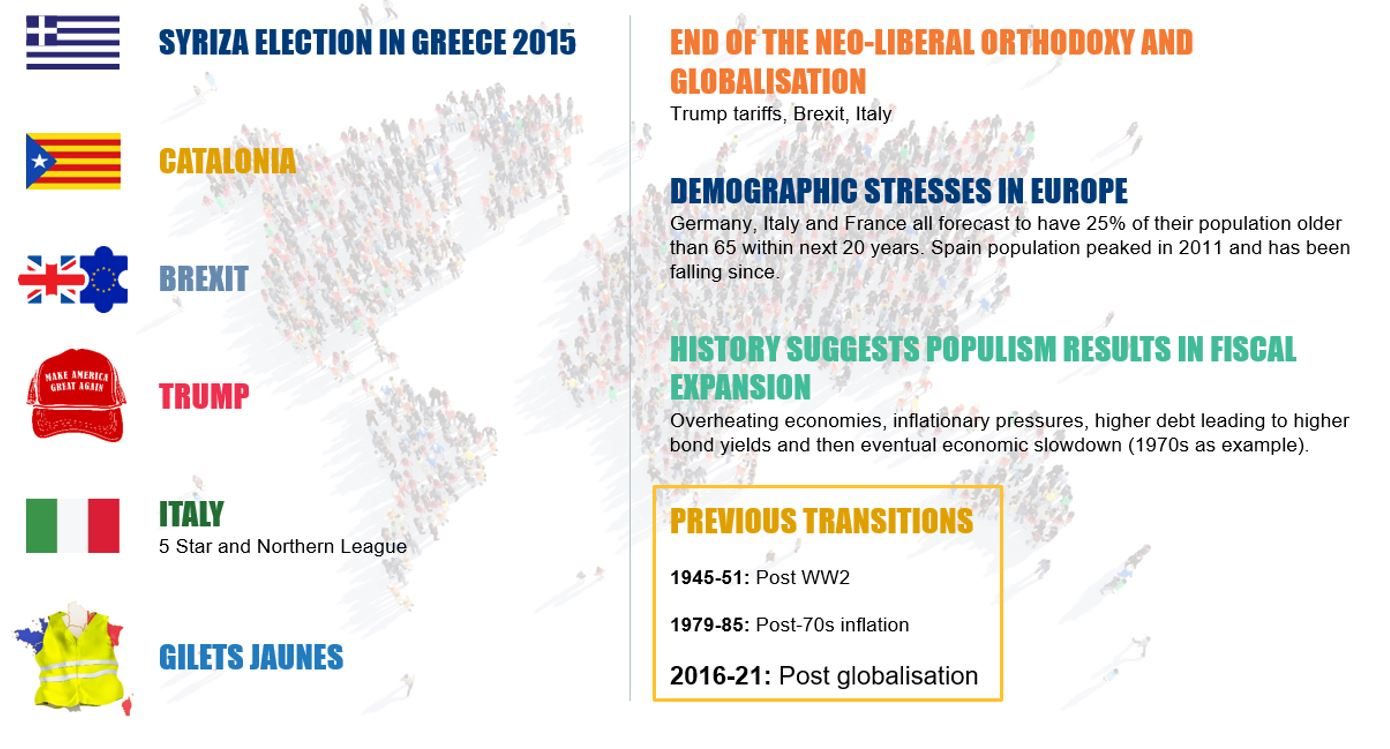

A series of events over the last five years have defined the continuing surge in populist movements. One of these was the election of Donald Trump as US president, and his administration’s subsequent protectionist policies which have included the trade dispute with China. However, the majority of these developments have taken place in Europe, where the overall populist vote share has risen from 7% in 1998 to over 25% in 2018.[4] Significant events in Europe have included the UK’s 2016 vote to leave the European Union, the formation of a populist government in Italy following an indecisive election result in March 2018, and, most recently, the ‘gilets jaunes’ protests on the streets of France.

Such developments indicate to us that we may be entering a new ‘post-globalisation’ era, which is likely to look very from different from the previous 30 years. In particular, history suggests that populist policies result in fiscal expansion, as governments are forced to consider radical new means of empowering their citizens. This can lead to inflationary pressures, higher debt (leading to higher bond yields) and, ultimately, an economic slowdown, as occurred in the UK in the 1970s. There is also a growing wave of support for what is being described as ‘modern monetary theory’ (MMT) or ‘helicopter money’. This centres on a belief that, as a government owns its currency, it can essentially run an infinite deficit to fund whatever it desires, because a public-sector deficit has always resulted in a private-sector surplus. However, such a policy could only work if central banks maintained interest rates at a very low level without sparking inflation.

From an investment perspective, this new era is likely to be very different from the previous 30 years. The global economic uncertainty index indicates that such uncertainty is now higher than at the height of the global financial crisis,[5] and, with the potential for further populist developments, it is likely that volatility will remain elevated. Furthermore, correlations between equities and bonds may continue to break down. Historically, this relationship has tended to see bonds perform better when equity markets have taken a dive and vice versa, acting as an important diversifier for multi-asset portfolios. However, in a more inflationary environment, there is potential for both asset classes to be weaker: inflation will naturally eat into fixed-income returns, but rising yields can also make the stocks of those companies with higher debt look less attractive compared with ‘safer’ securities. In such an environment, ‘growth’ stocks, which have driven much of the stock-market gains over recent years, may be less favoured, with ‘value’ equities making a comeback.

While the stimulus of recent years may have helped a rising tide to raise all boats, we believe we may now be entering a financial regime that is very different from the world we have become used to. In seeking to navigate this uncertain environment, we believe the importance of an active, flexible portfolio, with an eye to capital preservation, is likely to come to the fore.

[1] Source: US Census Bureau, 2017

[2] Source: Bloomberg, CPA London, March 2019

[3] Household wealth trends in the United States, 1962 to 2016: Has middle class wealth recovered?, Edward N Wolff, National Bureau of Economic Research working paper 24085, November 2017

[5] Source: http://www.policyuncertainty.com/, March 2019

This is a financial promotion. Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those countries or sectors. Please note that holdings and positioning are subject to change without notice.

Comments