Love it or hate it, and whatever your views on the contentious toast topper, it is unlikely you will have missed the Marmite controversy of last month, as Tesco ‘delisted’ the spread (along with dozens of other household-name products) following a price dispute with the British-Dutch manufacturer Unilever. As a result, Marmite was no longer available at Tesco online and in some stores as inventory levels started to run down.

So what pushed Tesco to such extreme lengths, potentially depriving the British public of many much-loved staples?

The answer lies with Unilever, the manufacturer. The multinational consumer goods company, which is co-headquartered in Rotterdam and London, wants to increase prices by roughly 10% following the steep devaluation in sterling after June’s Brexit vote, which has led to price rises in many of its inputs.

Tesco certainly played a clever PR game, positioning itself as a consumer champion in taking a stand against price increases. After all, these kind of negotiations go on behind the scenes between retailers and manufacturers all the time, so moving the spat (which was resolved just 24 hours later) into the public forum certainly helped its credentials as a consumer-focused business. The public’s fascination with the story was fuelled further by the press spinning the story as Tesco boss Dave Lewis (a former Unilever employee) taking on his old firm.

Tesco wasn’t the only company to receive a boost following the dispute; whatever Marmite and Unilever lost in terms of brand image in the controversy, they gained in public awareness, with sales of Marmite increasing by 61% for the week ending 15 October.[1]

The pricing on the cake

Many commentators asked why such price increases were necessary in the case of UK-manufactured products like Marmite, which is a by-product of British breweries. However, there are three main factors to consider, which are likely to hit manufacturers and retailers:

1. Unfavourable FX translations

For a company like Unilever, which reports its earnings in a foreign currency (in this case euros) yet is paid by the British retailers it sells to in sterling, these incoming pounds are now worth increasingly less in euro terms.

2. Commodities priced in foreign currencies

Many commodities which are vital to the manufacturing and distribution process – aluminium and polyethylene terephthalate for packaging, and oil for transportation and powering machinery – are priced in US dollars. The huge drop in sterling versus the dollar now makes these inputs more expensive.

3. The rising cost of cyclical agricultural products

Common agricultural inputs like dairy and wheat have in the recent past been at a low point in their cycle, leaving them very cheap. Now, it looks like the cost of these is starting to rise.

From ‘buy one get one free’ to bigger price tags

Currency hedging only delays the eventual impact on the staples manufacturers, allowing them breathing space to consider what they can do to mitigate the effects of currency fluctuations.

As such, it is inevitable that manufacturers will try to pass the cost on to retailers eventually.

To soften the blow of these price increases, manufacturers have a couple of options; they can innovate – make small changes in the product to justify charging a higher price – or re-engineer products – reformulate recipes or manufacture smaller packets at the same cost (perhaps with the positive spin that these are now ‘healthier’). But, nevertheless, price per gramme is likely to rise.

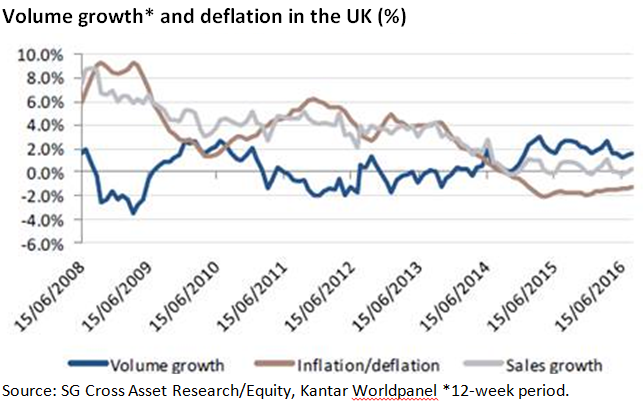

It is more than likely retailers will in turn be forced to push these price increases onto consumers. For the UK supermarket groups, it is already a tough environment. They have faced not only a deflationary environment and slowing sales growth (see chart below), but also the disruptive force of discounters increasingly taking market share.

However, certain strong brands are ‘must-haves’ for consumers (take Marmite for example) and to not stock such products risks losing customers. Therefore, while the retailers will fight to minimise price rises as much as they can, ultimately their low margins mean they will need to pass price increases on to shoppers. In the case of Marmite, this has already started to happen; just last week, WM Morrison, the UK’s fourth largest supermarket group, increased the price of a 250g jar of the sticky, salty spread by 12.5% to £2.64.

So, while the great marmite shortage of October 2016 may be over, it is clear that Britain’s decision to leave the European Union is likely to have significant ramifications for our pockets and our favourite products in the not so distant future.

[1] IRI: https://www.marketingweek.com/2016/10/25/marmite-sales-soar-as-tesco-price-row-bumps-up-brand-awareness/

Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell this security, country or sector. Please note that holdings and positioning are subject to change without notice.

Comments