Defined benefit (DB) pension schemes have one overriding objective: to be sufficiently funded to pay members their benefits on time and in full.

While the premise is straightforward, executing it successfully can be more problematic.

Volatile equity markets, asset prices stretched by loose monetary policy, and persistently low bond yields have made income yield harder to come by, while pension scheme retirees are living longer, and in increasing numbers.

These factors have led many schemes into cash flow negative territory or facing funding deficits, and in some cases both.

The growing negative cash flow predicament was highlighted in the UK by consultancy firm Hymans Robertson in its Trustee Barometer Report in 2015.[1]

The report revealed that half of the DB schemes within the FTSE 350 index are cash flow negative, with around £20 billion more going out in benefits than coming in from contributions per annum.

By 2030, the Hymans report estimates that the figure will have risen to £100 billion a year.

Pension freedoms bring uncertainty

The issues have been exacerbated by the UK government’s introduction of new pension scheme freedoms in April 2015. Under the changes, scheme pensioners are now able to access up to 100% of their pension pot in one go from the age of 55, bringing the ‘hump’ of the armadillo-shaped cash flows forward for many schemes, and creating an ever more urgent need for income.

The hunt for the yield to provide this income, and the need to address funding deficits, has led some DB pension scheme trustees to start looking beyond the conventional equities and bonds asset classes, towards alternative asset classes such as private equity and infrastructure, in an attempt to meet their income and growth requirements.

It is our contention, however, that by potentially replacing a portion of their global equity portfolio with other long time-horizon alternative assets in the hunt for capital and growth, schemes may be missing a far more conventional solution right behind them.

Traditions under pressure

For the majority of schemes, the traditional 60% global equity/40% fixed income portfolio remains the time-honoured method of portfolio construction. The bond component is there to provide the income and the equities component is there to provide the capital growth.

We believe it is time for schemes to take a less restrictive view on the role of equities within their portfolios.

Our view is that it may be an oversight to have 60% of scheme assets in non or low income-generating global strategies, when some of that could be better put to work in growth AND income-producing global equity income strategies.

If equity income is considered as a strategy in its own right, equities need not be in the portfolio purely to deliver capital growth, but could also help schemes to deliver on the other long-term scheme objectives – income for cash flow requirements and a recurring, reliable long-term return to serve the lifetime of the scheme.

That last point is an important one: global equity is in many schemes purely to deliver growth. However, because it is priced daily, and given the inherent volatility of the asset class, we believe short-term performance has become an obsession for many scheme managers who might find the short-term volatility hard to stomach.

While some managers might consider longer time horizon alternative assets to address this perceived short-term volatility, we believe they are overlooking the fact that equity income is less volatile than equity markets as a whole, and that, even if the capital value of the equity is falling, you are still being paid the income in most cases.

Taking a long-term perspective

We would argue that not only should managers consider adopting global equity income as part of their equity component, but also that they should stop thinking of it purely as a short -term growth solution.

It is our contention that global equity income be considered as an effective strategy over a longer-term timeframe in the same way private equity or infrastructure are, but with the added advantage of having greater liquidity, and the greater transparency that comes with investing in listed companies.

In our view, dividend payments should appeal to investors who may require a regular income for payouts, and if viewed as an integral part of the portfolio for the long term, global equity income may also offer reliable and steady capital growth to help schemes to deliver on their dual objective of generating income and growing capital over time.

Solid growth over the long term can offer scheme trustees reliable income for paying their beneficiaries, without having to seek out more alternative long-term investments, especially as when projected forward the combination of capital and income growth could be sufficient to meet schemes’ future funding requirements.

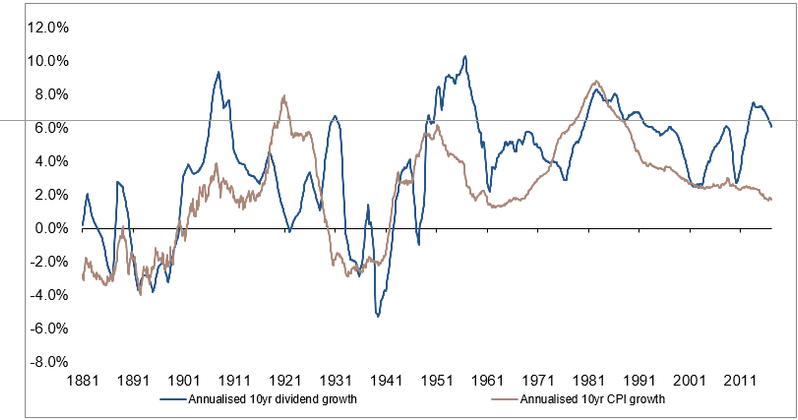

Global equity income can also offer a measure of protection from the threat of inflation over time. Research by SG Cross Asset Research measures dividend growth versus consumer price index (CPI) inflation all the way back to 1871. The chart below shows that dividend earnings growth over time tends to out strip CPI inflation, adding a further degree of protection against the erosion of returns over the longer term.

10 year annualised dividend growth v 10-year CPI inflation growth Jan 1871- Feb 2017

Source: SG Cross Asset Research/Equity Quant, Robert Shiller, February 2017

Last, but certainly not least, we believe recent research from the Pension Protection Fund, the Pensions Regulator, RiskFirst and Cambridge Associates[2] should add a further measure of reassurance to schemes concerned about how they will fund future payouts.

The research estimates that the average scheme pay-out peaks at less than 5% of scheme assets in any given year, and that the average UK DB scheme requires about 2% of its own assets under management to fund the benefits it pays out today.

The data reveals that even the UK DB scheme that was in the bottom quartile of performance would still only have to generate 7% income annually, to be able to pay up for the money going out of the door for the next 20 years.

For DB scheme trustees anxiously poring over future pay out projections and facing up to the reality of negative cash flow, these figures may provide reassurance that they do not need to feel overwhelmed by their future funding requirements.

By considering adding an element of global equity income into their schemes, and by viewing it as a long term investment, we believe they will have unearthed a highly liquid and uncomplicated solution, without the need to move up the risk spectrum in the hunt for income and growth. The global equity income solution may have been standing behind them all along.

[1] https://www.hymans.co.uk/news-and-insights/research-and-publications/research/trustee-barometer-2015-the-road-to-a-resilient-pension-scheme/

[2] Presentation by Cambridge Associates: Managing Pension Scheme Liquidity – The Long View. 9/1/17. Data taken from the Pension Protection Fund, the Pensions Regulator, RiskFirst and Cambridge Associates.

Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those countries or sectors.

Comments