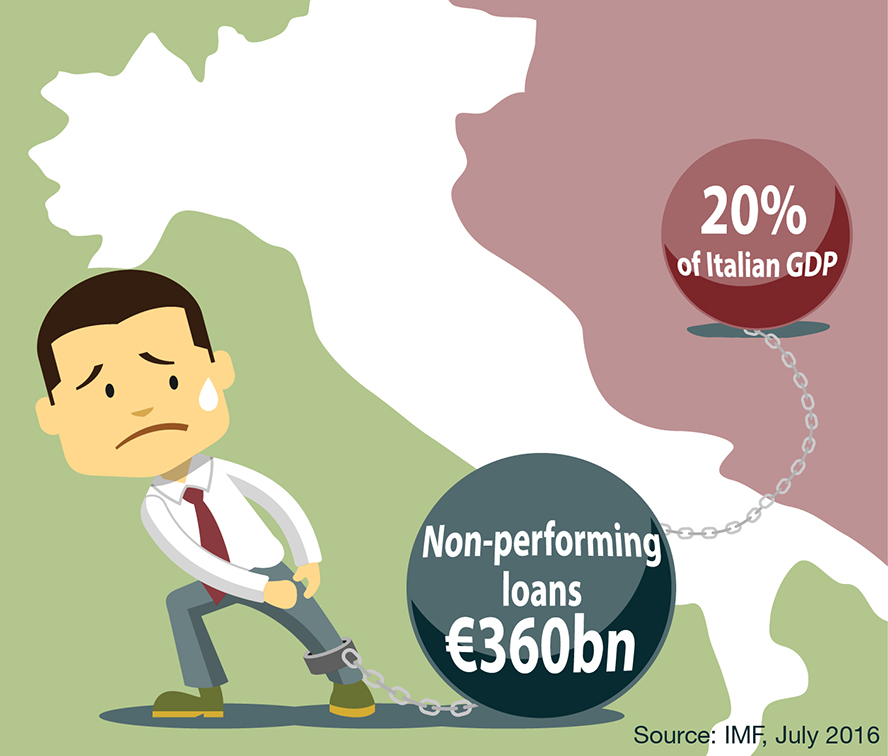

The pressure on European banks which has dogged the sector since the global financial crisis is now focused on Italy, where banks are struggling to deal with their mounting burden of non-performing loans (NPLs), which now amount to around €360 billion – some 20% of Italian GDP.

The pressure on European banks which has dogged the sector since the global financial crisis is now focused on Italy, where banks are struggling to deal with their mounting burden of non-performing loans (NPLs), which now amount to around €360 billion – some 20% of Italian GDP.

The Italian banks never really properly cleaned out their NPLs after the post-financial crisis recession, with bad loans continuing to accumulate in Italy’s corporate and small business segments (while household debt leverage actually remains quite low), as companies continue to struggle with a lack of competitiveness in euro-denominated trade terms.

Despite recent bankruptcy reforms, the legacy legal process for resolving such bad debts is complicated and time-consuming, meaning that bad debt issues persist for several years and losses tend to accumulate to a high percentage of loan values. Sector-wide loan loss provisions against NPLs are woefully inadequate, leaving the Italian banking sector with a considerable capitalisation problem given the provisions that still need to be recognised against past bad loans. This problem is exacerbated by the system’s low level of profitability, which means that such capital needs to come from external sources rather than through the banks’ internally retained earnings.

Somewhat ironically, we see the Italian banks as being particularly punitively affected by the European Central Bank’s (ECB’s) negative interest-rate monetary policies (despite the opposite intention), given the deposit-heavy nature of the banking system’s liabilities and an industry convention for loan pricing that is directly linked to market rates.

However, we would stress that not all banks should be tarred with the same brush. These comments refer to the Italian banking system in general, rather than to all Italian banks. Some banks have proactively dealt with their NPLs and reorganised their businesses to structurally improve go-forward profitability despite the tough external backdrop.

Must do better

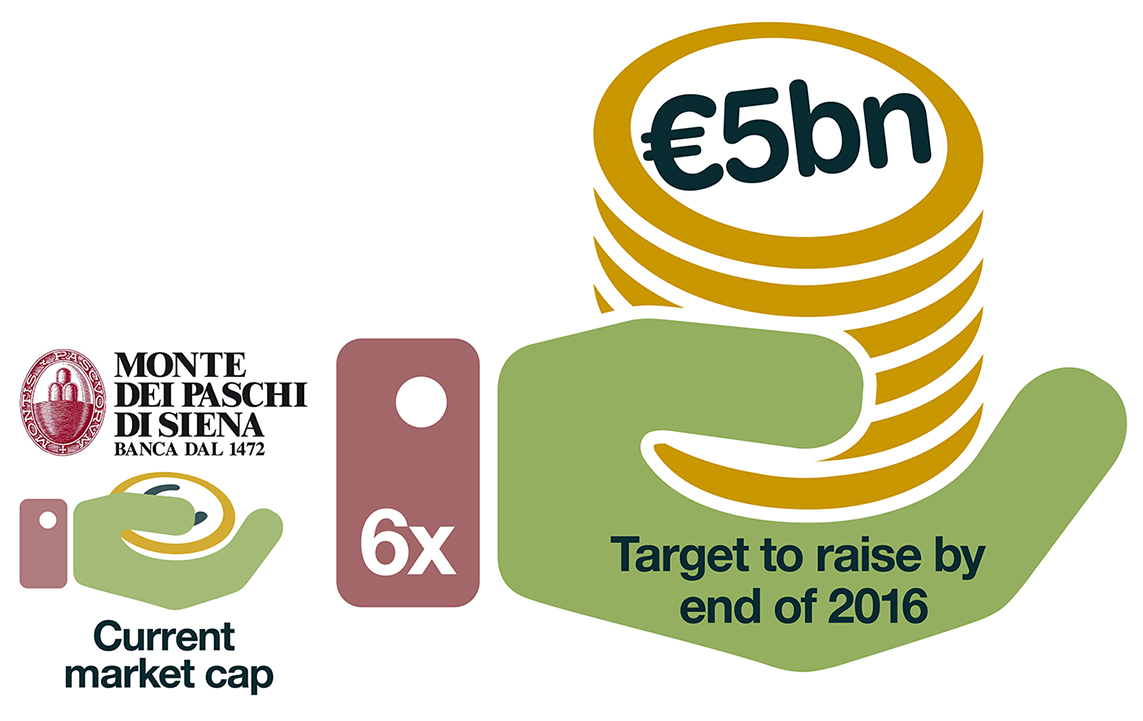

Perhaps the poster child for these problems is Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena (MPS), the world’s oldest surviving bank, which has perennially faced the circular issue of low profitability, high NPLs and concerns over capital levels. In the recent European Union (EU) stress test, MPS’ core capital ratio declined to -2.4% in the adverse case scenario, indicating the bank’s inability to remain solvent through a period of stress. This resulted in MPS announcing a “structural and definitive solution to [its] bad loan legacy”. This involves divesting its €27 billion NPL portfolio into a securitisation vehicle and raising up to €5 billion in fresh capital through a rights issue by the end of 2016, with a new strategic business plan to be presented in September 2016. [1]

However, there are doubts over the likely success of this plan, most notably the capital raise, which stands at over six times the firm’s current €715 million market capitalisation. Many investors are still licking their wounds after supporting MPS through numerous capital infusions since the financial crisis under the mistaken belief that each capital raise would be the last. These investors include the Monte dei Paschi di Siena Foundation, which has seen its stake in the bank diluted to 1.49%, leading to a dramatic curtailment in the foundation’s ability to support charitable causes in Siena.

However, there are doubts over the likely success of this plan, most notably the capital raise, which stands at over six times the firm’s current €715 million market capitalisation. Many investors are still licking their wounds after supporting MPS through numerous capital infusions since the financial crisis under the mistaken belief that each capital raise would be the last. These investors include the Monte dei Paschi di Siena Foundation, which has seen its stake in the bank diluted to 1.49%, leading to a dramatic curtailment in the foundation’s ability to support charitable causes in Siena.

Between a rock and a hard place

In the past, such bank solvency issues would have been solved through some form of government support, such as in the case of the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) in the US in 2009, the UK government’s bailouts of Royal Bank of Scotland and Lloyds, or the bailout of the Spanish banks in 2012.

However, in January this year the EU introduced the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRBD), which prevents the Italian government from using state funds to recapitalise the banking system without first bailing in bank shareholders and creditors, forcing them to take a loss on their holdings. An 8% bail-in of a bank’s total liabilities – the minimum that must be bailed-in before public funds can be used to recapitalise the banking system – would wipe out junior bond holders entirely and inflict severe losses on the holders of senior debt. The problem in Italy is that as bad debts mounted, banks sought to raise fresh capital by selling subordinated bonds to their own retail customers, pitching them as a higher-yielding alternative to deposits, but just as safe. Italian households now own about one third of senior bank debt and almost half of subordinated debt, equal to about €230 billion. [2]

However, in January this year the EU introduced the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRBD), which prevents the Italian government from using state funds to recapitalise the banking system without first bailing in bank shareholders and creditors, forcing them to take a loss on their holdings. An 8% bail-in of a bank’s total liabilities – the minimum that must be bailed-in before public funds can be used to recapitalise the banking system – would wipe out junior bond holders entirely and inflict severe losses on the holders of senior debt. The problem in Italy is that as bad debts mounted, banks sought to raise fresh capital by selling subordinated bonds to their own retail customers, pitching them as a higher-yielding alternative to deposits, but just as safe. Italian households now own about one third of senior bank debt and almost half of subordinated debt, equal to about €230 billion. [2]

Epic bail

To bail-in the households that make up a large part of the capital base of Italian banks would be politically toxic. When the government enforced the bail-in of four of Italy’s smallest banks last year, thousands of shareholders and retail bond holders were wiped out, resulting in a political backlash against Prime Minister Matteo Renzi. Widespread bail-ins of Italy’s household savers would almost certainly lead to Renzi losing the October referendum on parliamentary reform, a result upon which Renzi has pledged to tender his resignation.

The problem for those European bureaucrats who argued for the introduction of the BRBD is that they need Renzi in power. Not only is he pro-EU, he has been a source of political stability, a rare commodity in a country where the average tenure for a prime minister has been around nine months in the post-war period. Renzi has been able to push through some of the reforms seen as necessary to restoring Italy’s economic competitiveness. If household depositors are bailed-in, not only would it be the end of Renzi, it would also fuel a rise in anti-EU sentiment among the Italian population whose support for the EU project is already faltering. This could see the Eurosceptic Five Star Movement take the reins of power, increasing the risk of another member state looking to extract itself from the union, only this time it would be a fully-fledged member of the currency bloc.

Going round in circles

While the ECB remains willing to supply cheap liquidity to Italy’s banks, the risk of a systemic crisis continues to be suppressed, but it does nothing to resolve the underlying issues that hobble the Italian economy.

Without a full-scale clean-up of bank balance sheets, there is little chance that Italian banks will be able to resume extending new credit to the small business sector which is crucial to the Italian economy. And without a recovery in lending to the small business sector, there is little chance that Italy will be able to generate a rate of growth sufficient to arrest the worsening of bank NPLs. In order to escape this negative feedback loop that is hampering Italy’s escape from its economic malaise, a systemic solution to the large NPL stock is necessary; otherwise the already disappointing economic recovery is likely to slow further.

With thanks to Brendan Mulhern our resident strategist for his input into this piece.

[1] Monte dei Paschi di Siena, 30 July 2016: http://english.mps.it/media-and-news/press-releases/ComunicatiStampaAllegati/2016/Press_Release_ENG_DEF.pdf

[2] IMF Country Report No. 16/222, July 2016: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2016/cr16222.pdf

Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell this security, country or sector. Please note that holdings and positioning are subject to change without notice.

Comments