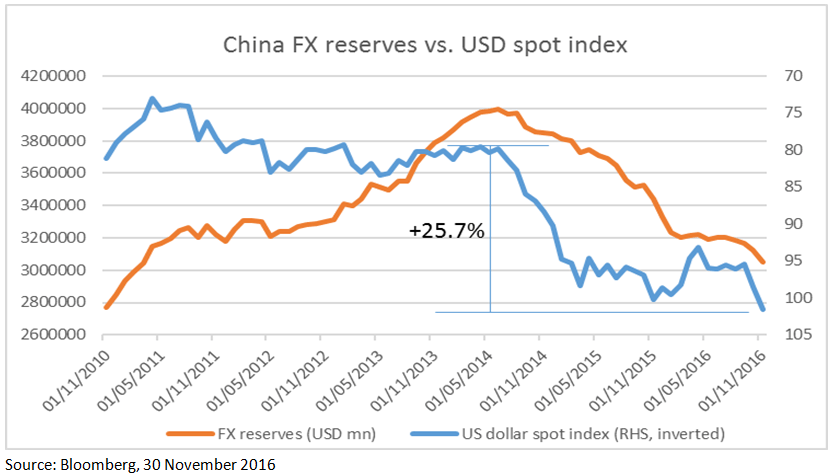

This month saw confirmation of accelerated capital outflows from China, with headline foreign-exchange (FX) reserves falling $69bn in November (up from $46bn in October), the largest monthly drawdown since January and above the $60bn decline which had been forecast.

A portion of this decline is attributable to valuation effects from the strong US dollar and falling bond prices. However, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) has undoubtedly been intervening more forcefully since last month’s surprise US election result triggered a resurgence in the dollar and expectations of rate increases from the Federal Reserve.

The end of November saw the State Council announce new restrictions on Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) and mergers & acquisitions (M&A) – common pretexts for capital flight – in an attempt to stem the tide of outflows. These new constraints, which mean greater government agency approval for FDI and M&A activity will now be required, certainly smack of renewed anxieties about renminbi weakness.

Indeed, China’s large base money supply (close to $22.4 trillion and over 200% of GDP) ensures curbing capital and depositor flight is key to containing systemic financial risks. Thus, we expect further capital account restrictions (perhaps including forced repatriation of dollar export earnings and limitations on households’ annual FX purchase quotas, currently set at $50k) in the event of continued US-dollar strength. Nonetheless, there are some important sources of comfort worth highlighting.

Policy prudence?

In a recent paper assessing reserve ratio adequacy, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) indicated FX reserves of 5% and 10% of broad money supply (M2 – cash and checking deposits as well as highly liquid assets such as savings deposits and money-market securities) were consistent with financial stability for countries with fully open and closed capital accounts respectively.[1] The IMF also acknowledged there was empirical evidence of the effectiveness of capital controls in limiting the flow of money overseas. Thus, while the efforts of China’s State Council to restrict outflows suggest growing nervousness, they also point to policy prudence.

Moreover, China’s current FX reserve position of $3.05 trillion (13.6% of M2) remains well above IMF guidance on reserve adequacy ratios (aside from circa $750bn in sovereign wealth fund assets). A further drawdown in reserves to IMF threshold guidance levels for countries with a fully closed capital account would entail a decline in China’s FX buffers to $2.2 trillion. In other words, capital outflows can be maintained at the current pace for the next 12 months without breaching IMF-prescribed adequacy levels.

Were we to be more generous in our assessment of China’s current FX regime, accepting that a managed USD/CNY float has been in place around a stable trade-weighted currency basket since August of last year, the advised capital cushion would fall to around $1.7 trillion (7.5% of M2). Furthermore, and as the chart below illustrates, China’s reserve drawdown to date (from a peak of $3.99 trillion in June 2014) has been combined with a +25% US-dollar rally. Should this relationship hold (i.e. remain more about dollar strength than renminbi weakness and depositor flight), further appreciation of around 20% in the US-dollar spot index (also known as DXY) could see China retaining adequate reserve levels around the $2 trillion dollar mark. But such an extended DXY appreciation would be consistent with a normalisation of US interest rates to pre-global financial crisis levels, a prospect which remains challenging given still-elevated debt levels, (for now) modest inflation, and the need to complement proposed fiscal stimulus with low borrowing costs.

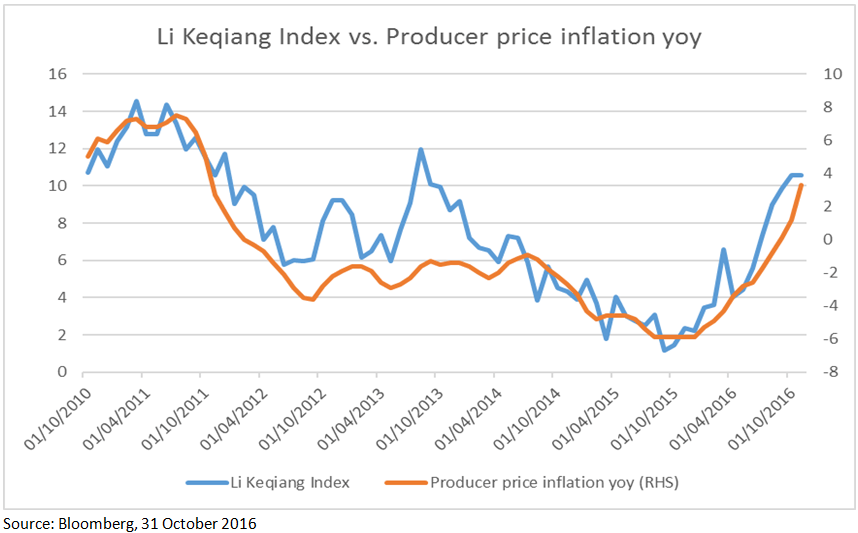

Furthermore, China’s current macroeconomic backdrop appears considerably more positive than was the case 12-18 months ago, with growth and deflation pressures (as illustrated below by the Li Keqiang index[2] and year-on-year producer price indices) witnessing notable turnaround since Q4 2015.

A new paradigm for emerging markets

However, we are not complacent. The abrupt transformation of the US political landscape, associated monetary/fiscal stimulus rebalancing, and potentially reduced US import propensity have increased the likelihood of further DXY strength, representing a challenging new paradigm for emerging markets in general – China included.

So, with the greenback boosted by renewed US growth expectations following last month’s presidential election, renminbi (and broader emerging-market FX) depreciation and capital flight risks have risen, while a cooling property market and Beijing’s recent tempering of stimulus renders softer Chinese growth a possibility in the first half of 2017. Hedges against China-related market jitters into the new year therefore remain prudent.

As such, we remain long US dollars in fixed-income strategies, as well as holding short Korean won and (modestly) long Japanese yen positions, thereby hedging potential renminbi-related financial market stress.

Nonetheless, China’s notably firmer near-term growth backdrop, increased capital controls and adequate FX reserve levels, suggest the State Council’s explicit prioritising of economic stability (at the expense of reform) ahead of next autumn’s 19th National Congress remains plausible.

[1] http://www.imf.org/external/np/spr/ara/

[2] The Li Keqiang index measures China’s economy using three indicators: railway cargo volume, electricity consumption and bank loans.

Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those countries or sectors. Compared to more established economies, the value of investments in emerging markets may be subject to greater volatility owing to differences in generally accepted accounting principles or from economic or political instability or less developed market practices.

Comments