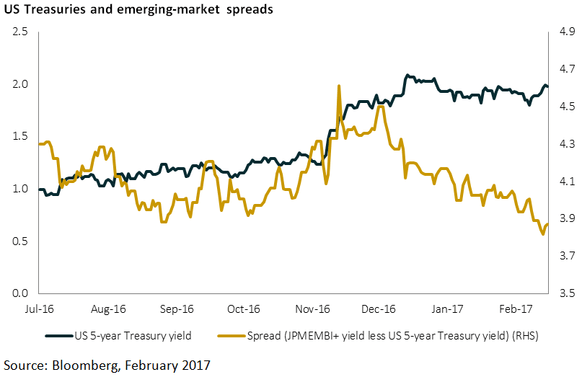

Amid the hoo-ha surrounding Donald Trump’s election in November, emerging-market bonds sold off markedly, but in recent weeks their overall yields have been moving lower and spreads (yield premiums) over high-quality government bonds have been tightening. Negative price action has been seen in the underlying US Treasury market instead – see chart below.

In an absolute-return sense, and with a view to keeping an eye on downside protection, we believe that much of the emerging-market bond asset class is better left watched for the time being.

The case for hard-currency, short-dated bonds

At the moment, we favour hard-currency (not local-currency), shorter-dated bonds. We do hold some lower-rated names, but these relate to issuers that do not have onerous debt obligations falling due over the next couple of years, most of which could sit tight for a while if the markets were to become turbulent.

There is nothing particularly profound in this, given that generally every man and his dog wants short-dated US-dollar-denominated issuance; in a rising US rate environment, investors are loath to take on US interest-rate exposure with long-duration US-dollar-denominated debt. However, it’s an approach that we believe offers scope to pick off some of the recent issuers which, while having poorer creditworthiness, have already covered all of (or the bulk of) their issuance requirements for 2017 in the first few weeks of the year.

Taking into account debt profiles, foreign-exchange reserves and other measures such as import coverage, we think that these bonds should be fine to weather a storm. If these measures remain robust, short-duration bonds will pull to their par redemption value as they approach maturity, even if sentiment turns negative, and the scope for negative performance should be limited.

Trade winds

Donald Trump has stated that he believes the US dollar is too strong and is hurting US exporters. However, the bulk of the policies he has espoused so far would be conducive to further US-dollar strengthening, especially versus emerging-market currencies. Trade tariffs on imports, and the onshoring of industry (e.g. car manufacturing), are likely to result in a stronger dollar, higher inflation and higher US base interest rates.

These conditions have traditionally presented a difficult backdrop to emerging-market government debt markets; back in 2014 and 2015, together with concerns over the viability of the Chinese economic model, they were a significant headwind to the asset class. Some of these fears have dissipated, owing to improvement in global trade, a reduction in some very large fiscal and current-account deficits, and an adherence to more conformist policymaking in the majority of major emerging-market debt-issuing economies.

While we believe investors have overlooked some of these concerns in relation to hard-currency emerging-market government debt, the above factors have tempered our appetite somewhat to embrace local-currency-denominated debt in a period of US-dollar strength, despite the higher yields on offer.

Looking ahead

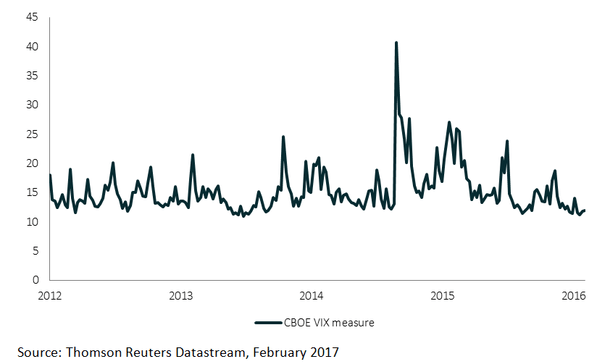

In common with volatility gauges on other markets (including oil for example), the VIX index, a measure of US equity-market volatility, has failed to reflect the possibility of greater instability in 2017, having remained around the lows of the last three years, as the chart below shows.

President Trump has suffered a few recent rebuffs in pushing through aggressive policy decisions. It remains to be seen whether future policy will tend towards greater toeing of the line or whether Trump redoubles his efforts. Based on previous reactions, our expectation would be towards the latter.

Between Trump’s election victory and his inauguration, market participants were speculating as to whether the approach of campaign-trail Trump would be reflected in the approach of President Trump. Everything we have seen now leads us to believe that the answer to that question is yes. This is now a ‘known unknown’, and yet it has had a muted reaction in financial markets.

In the context of limiting downside risk, we need to be mindful that potential volatility in risk assets and the US Treasury market, coupled with uncertainty about the pace and scale of US interest-rate increases, rising global inflation and the likelihood of a stronger dollar, should reasonably be causing emerging-market government bond spreads to widen, not tighten. That leads us to be cautious and to keep our powder dry for what we think will be better buying opportunities.

Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in that security, country or sector. Compared to more established economies, the value of investments in emerging markets may be subject to greater volatility due to differences in generally accepted accounting principles or from economic, political instability or less developed market practices.

Comments