In early 2016, the authorities appeared to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat. According to the World Bank, 2015 saw only the sixth year-on-year contraction in world GDP in nominal US-dollar terms since records began in 1960. Not only that, but the annual decline was the largest on record, at -5.5%, eclipsing even the fall of 2009. Industrial commodities were collapsing, emerging-market equities were in the throes of a bear market, while yields on emerging-market debt were marching higher, as footloose international capital took flight.

However, it wasn’t just emerging markets where prospects were taking a turn for the worse. By early 2016, developed-market (ex US) equities were also firmly in a bear market, while high-yield credit spreads in the US were blowing out.

While the financial and economic stress had its locus in China and emerging markets, the catalyst was arguably the US Federal Reserve’s (Fed) winding down of the third round of its quantitative-easing programme. This reduced the supply of central-bank liquidity to the global financial system which, alongside the significant appreciation of the US dollar from mid-2014, led to a massive tightening of global liquidity conditions.

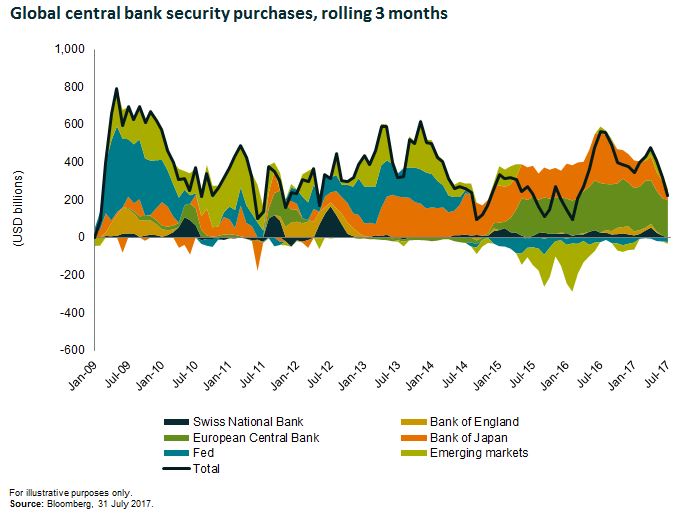

Liquidity conditions have a habit of leading the ‘real’ economy. As cash flows deteriorated in 2015, points of balance-sheet vulnerability within the global financial system were exposed. In the face of mounting financial stress that looked set to have serious economic repercussions, the authorities responded. The Fed stepped away from further rate hikes and talked down the dollar, while the European Central Bank (ECB) ramped up its own bond-buying programme. Capital flight from China and emerging markets abated, and by mid-2016 global central banks were supplying more liquidity than at any point since immediately after the global financial crisis.

A new inflection point?

But why does this episode warrant revisiting? Because, once again, believing the global economy to be on firmer ground, the world’s major central banks are now set to begin withdrawing monetary support.

Following their collective efforts, global liquidity conditions have been supportive of economic activity and financial markets throughout 2017, but there is reason to believe that we may be on the cusp of an inflection point when it comes to liquidity. While central banks have collectively purchased around $2 trillion of assets this year, the pace has already been declining as the Bank of Japan has reduced its monthly asset purchases in favour of ‘yield-curve control’. Central-bank liquidity provisions are set to fall further as the Fed begins the process of reducing its mammoth balance sheet, while the ECB is potentially set to taper its monthly purchases further.

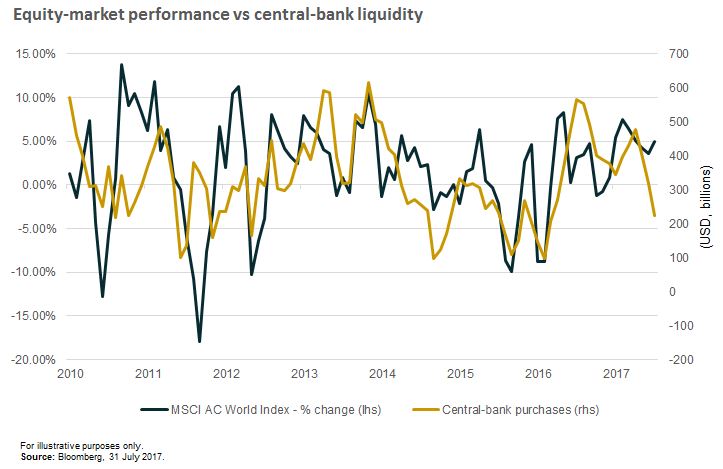

The question facing investors is whether asset prices, successfully inflated with central-bank liquidity injections, can maintain rarefied levels even as that same liquidity is withdrawn. Or will the relationship between central-bank liquidity and risk assets break down?

My view is that reduced supply of central-bank liquidity, whether through reduced purchases or balance-sheet reduction is, in the absence of a private sector that is willing to increase leverage as in pre financial-crisis days, axiomatically deflationary, as I discussed in an earlier blog post. In due course, I believe this is likely to undermine support for risk assets, and in turn provide a further tailwind for government bonds.

Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those countries or sectors. Please note that holdings and positioning are subject to change without notice. Compared to more established economies, the value of investments in emerging markets may be subject to greater volatility owing to differences in generally accepted accounting principles or from economic, political instability or less developed market practices.