Since the onset of the global financial crisis in 2008, the scale of emerging-market debt has grown rapidly. What does this mean for investors who have been encouraged by low developed-world bond yields to seek better returns from such asset classes?

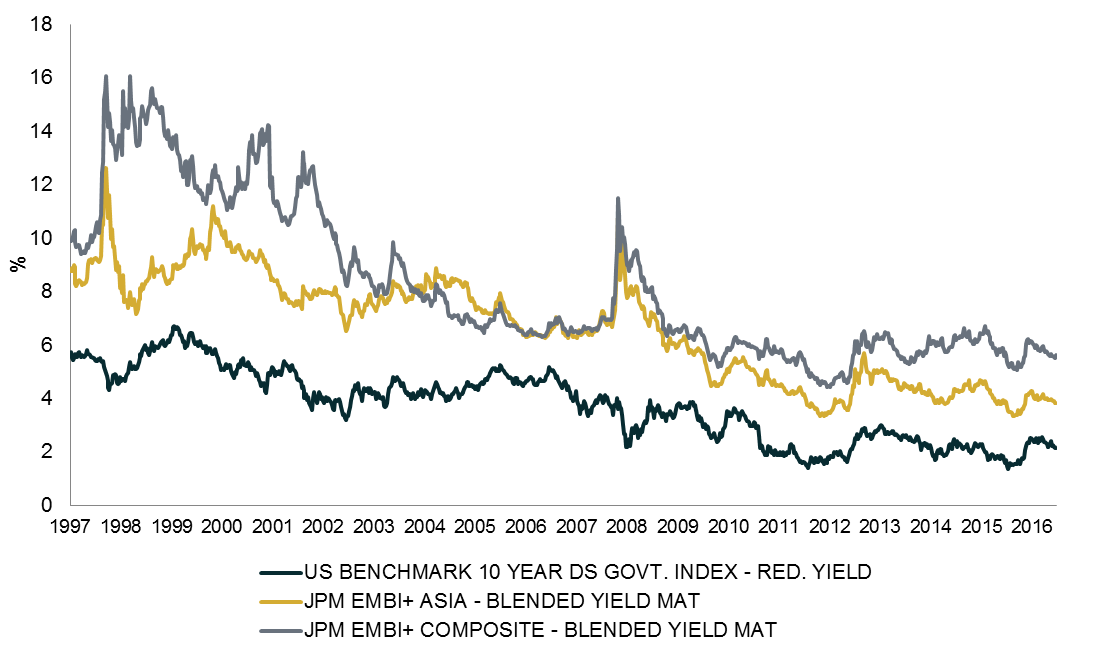

With global recovery proving to be very gradual, and wage inflation muted – despite unemployment rates returning to normal levels in countries further along in the recovery process (such as the US, UK and Japan) – core inflation has also remained mostly subdued in developed markets.

Monetary policy has consequently remained very loose. In addition, expectations for an acceleration in growth have been repeatedly disappointed in the last few years, providing ammunition to the proponents of the ‘secular stagnation’ theory, which has arguably contributed to the flattening in developed-market sovereign yield curves. As a result of this, developed-market bond yields have moved progressively lower, encouraging investors to go on a ‘hunt for yield’.

Chart 1: US 10-year Treasury yield vs. JPM EMBI+ Composite, JPM EMBI+ Asia

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream, July 2017

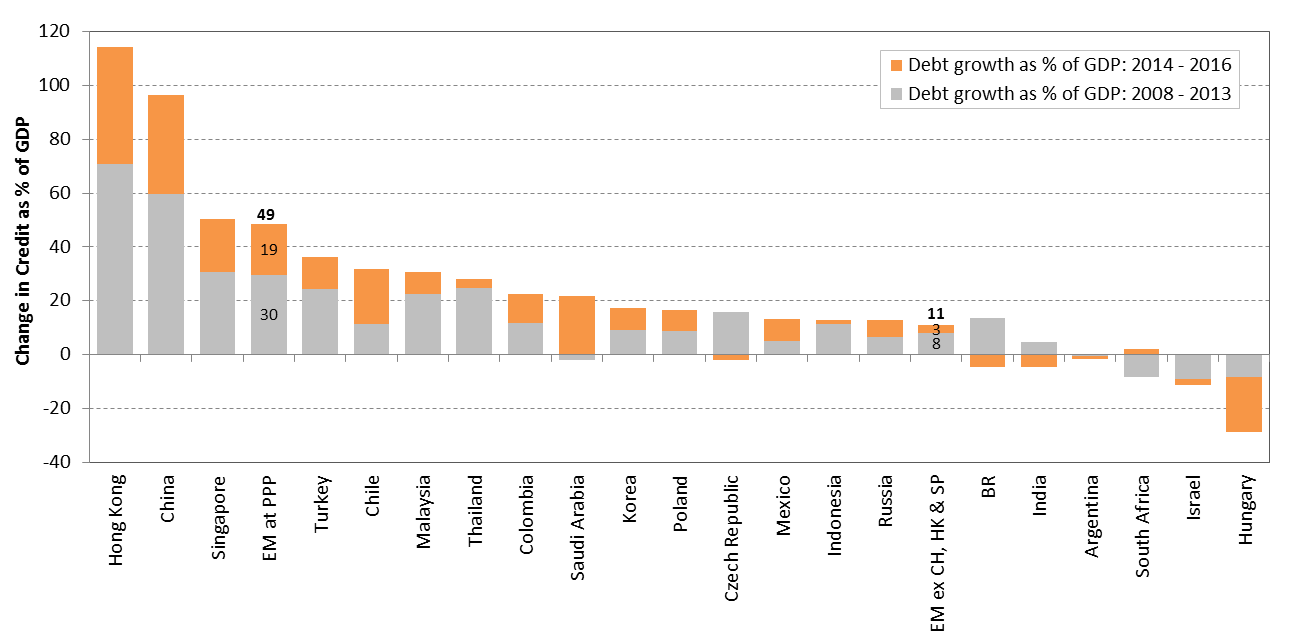

Considering the Bank for International Settlements’ (BIS) measure of emerging markets’ gross government debt as a percentage of GDP at purchasing-power parity (PPP), emerging-economy debt has risen from 36% in 2008 to 47% at the end of 2016 – a sizeable move. Private non-financial sector credit growth was even stronger, increasing by an eyebrow-raising 49% of GDP (from 80% to 129%).

There is, however, substantial variation in the credit growth that has occurred between different emerging markets.

China obscures much of the picture, given its significant and growing economic size, coupled with how fast credit has grown there over the last eight years. According to BIS, Chinese private non-financial sector debt had rocketed up by 96 percentage points to 210% of GDP at the end of 2016. While denoted as ‘private’, much of this debt is attributable to state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Household debt accounts for just 45% of GDP, with the balance being non-financial corporate debt, which accounts for the majority of the debt growth since 2008.

Excluding China, Hong Kong and Singapore, private non-financial sector debt in emerging markets has only risen by 11% of PPP-weighted GDP, from 63% in 2008 to 74% at the end of 2016. This shows that, once China is excluded, the rise in emerging-market debt has been far less dramatic than is often perceived. Growth in private non-financial debt as a percentage of GDP since 2008 is shown in chart 2 for various emerging markets. While generally increasing for most, only Turkey, Chile, Malaysia, Thailand and Colombia have seen debt-to-GDP growth of more than 20 percentage points over these eight years.

Chart 2: Private non-financial debt as a % of GDP

Source: Newton, Thomson Reuters Datastream, BIS, July 2017

What has also been noteworthy is that, since the ‘Taper Tantrum’ in May 2013, when the then US Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke surprised markets by announcing that the monthly volume of asset purchases was likely to be trimmed in future months, there has been substantially slower credit growth in the emerging-markets group that excludes China, Hong Kong and Singapore than in the inclusive emerging-markets group. This is illustrated in Chart 3, which shows that debt as a percentage of GDP at PPP has only risen by three percentage points since the beginning of 2014.

Chart 3: Private non-financial debt as a % of GDP: 2008 – 2016

Source: Newton, Thomson Reuters Datastream, BIS, July 2017

Slower domestic growth in a number of these economies as a result of commodity-price weakness meant slower domestic credit growth as well, meaning some rationalisation of credit growth has already taken place in a number of countries over the last three years.

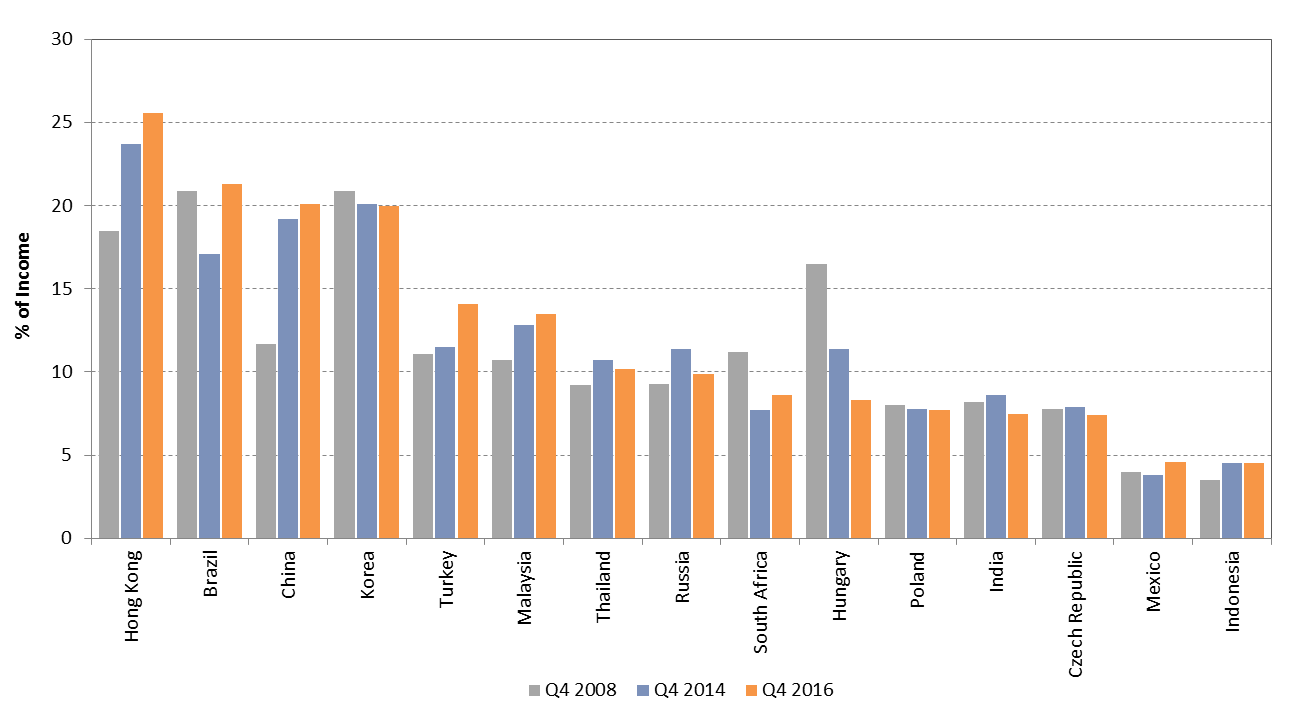

Chart 4: Private non-financial debt service ratios

Source: Newton, Thomson Reuters Datastream, BIS, June 2017

There are some specific cases where debt has risen quickly since 2008.

- Colombia: In Colombia’s case, while debt has risen rapidly, it has come from a low level, making it potentially less concerning. The country has been through a painful slowdown following the collapse in the oil price in 2014, but seems to be coming out of the worst of this now, having allowed its exchange rate to move freely, thus easing economic adjustment. A further fall in the oil price could complicate matters, as this would weaken the exchange rate and keep price pressures elevated.

- Turkey: While Turkey’s debt-to-GDP ratio is also coming from a low level, the speed and scale of debt growth – 36% of GDP over the last eight years – is potentially more worrying, when viewed alongside the country’s persistent large current-account deficit, which leaves it heavily reliant on foreign financing. Added to this is an increasingly autocratic government, which has frequently appeared to interfere with prudent monetary policymaking at the central bank. This may serve to increase the risk of capital flight when some unforeseen shock arrives in future.

- Malaysia: Has also seen very rapid credit growth, with gross government debt to GDP rising by 14% of GDP and non-financial private sector debt by 31%. While GDP growth has reaccelerated since the slowdown in Q1 2016, this remains a risk to watch.

- Thailand and South Korea: Have seen significant credit growth over the last eight years, but this has slowed down notably over the last two years. GDP growth rates have bottomed out, with exports growing solidly, thus lessening immediate concern. Also, because interest rates have fallen considerably, debt service ratios (the amount that has to be paid back in principal and interest each year as a percentage of income) have remained relatively unchanged – as seen in Chart 4 above.

Other emerging-market countries have generally seen much more sedate credit growth, with a few undergoing deleveraging, such as Hungary, and to a lesser extent South Africa. Referring back to Charts 2 and 3, India has had very slow credit growth for a while now, with private non-financial sector credit to GDP unchanged from 2013 to 2015 and falling last year. This has been largely because of slowing economic growth with overcapacity in the private sector limiting the need for new investment, coupled with a large state banking sector that needs to raise capital before it can lend more. However, these issues are likely to be transitory, leaving plenty of scope for credit to support growth in coming years.

Similarly, Indonesia and the Philippines (not shown) both have low private-sector credit-to-GDP ratios, coming from a lower level of financial development, but with ample room for further credit penetration in future. With these countries’ economies being primarily domestically driven rather than mainly dependent on trade, this adds to the strong demographic profiles of both, supporting much higher potential GDP growth than for many others.

In conclusion, while the headline level of private sector debt for emerging markets has appeared to grow very rapidly, most of this is attributable to China, with considerable variation between the remaining countries. We will continue to watch debt growth in emerging markets, particularly in view of the fact that the Federal Reserve has begun raising interest rates, but on balance we think the risks are manageable for now.

Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those countries or sectors. Please note that holdings and positioning are subject to change without notice. Compared to more established economies, the value of investments in emerging markets may be subject to greater volatility owing to differences in generally accepted accounting principles or from economic, political instability or less developed market practices.

Comments