Under the new US administration, it is likely that we will see the most fundamental overhaul of the US tax system in generations. Both Donald Trump and Republicans on the Ways and Means Committee of the House, through their tax blueprint, have suggested radical, albeit different, changes to the US corporate tax system.

By taxing worldwide earnings at a rate of 35%, the US tax system as it stands is highly punitive for any businesses with profits in the US; it incentivises international companies to keep earnings offshore/permanently invested abroad, away from the grasp of the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

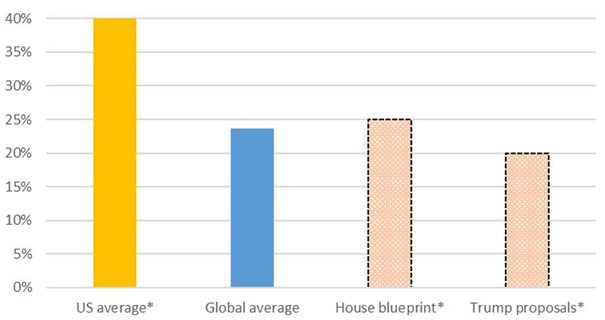

Global corporate tax rates

* US corporate tax rates include an average state rate of 5%

Source: KPMG, Newton

A key pledge of Trump’s election campaign was the creation of 25 million new jobs in America, which will require significant incentives. In his inauguration speech, Trump stated: “We will follow two simple rules: buy American and hire American.

Clearly, any ‘protectionist’-type reform aimed at incentivising companies to repatriate their production to American soil has wide scale implications for the global economy and free trade. It is important to bear in mind that any tax cut needs to be funded, so there are also implications for the dollar, interest rates and inflation.

To put everything into context, corporate tax represents around 10% of US tax receipts, the equivalent of 2.5% of US GDP. The average tax rate in the S&P 500 is circa 30%, but not all of this is subject to US tax. A very optimistic scenario, in which the average tax rate falls to 25%, would justify an 8% increase in the value of US equities, all other things being equal.

While the macroeconomic outcomes are debatable, what is clear is that there will be a wide variation of impact at the company level. Here we address the practical question of how to identify whether the proposed reforms represent a risk or opportunity at the stock level.

The proposals

Commentators ascribe a 65% chance of tax reform being enacted in the US before the end of the year. The main points of both the House’s blueprint and Trump’s plans are to:

- Lower the tax rate. A reduction in the federal corporate tax rate to 15% (Trump) and 20% (House blueprint). In addition, state taxes will continue to apply at an average rate of 5%.

- Incentivise US production. Under Trump’s proposals there is an import penalty, likely to be some form of tariff. Under the House blueprint there is both an import penalty and export support; the mechanism for doing this is known as the border-adjustable tax.

- Remove interest deductibility. Remove the deductibility of interest payments in the US for new debt.

- Accelerate tax depreciation. Immediate depreciation for tax purposes of capital expenditure in the US.

- Remove tax credits. A quid pro quo for reducing the tax rate.

- Encourage repatriation of cash. One-time repatriation of cash to release trapped cash from overseas at a reduced rate.

The big picture is that, under either Trump’s mooted reforms or the House blueprint, the net impact on the tax charge is a balance between three factors: a lower tax rate, the import penalty and export support (under border adjustment). The impact of the other proposals is in general more minor.

The practical challenges of estimating US costs

The big practical challenge for investors in assessing the impact of these proposals will be to analyse the geographic split of costs at the company level and attribute them accurately. Transfer pricing, which is not seen in the consolidated accounts, adds further complexity to this assessment. The border-adjustment proposal has the effect of cancelling out any benefits of transfer pricing from the US perspective, thereby removing the effectiveness of such schemes used to divert profits away from the scope of the IRS.

|

Take the fictitious example of Bacchus Stores, a US wine merchant. Bacchus Stores sells 1,000 bottles of wine a year domestically for $100 a bottle and makes a profit of $20 a bottle. Bacchus Stores has sales of $100,000 and pre-tax profits of $20,000. As Bacchus Stores only sells bottles of Stuber Estate from California and it is taxed at the full US federal rate of 35%, this results in a tax charge of $7,000. Given its roaring success, Bacchus Stores undertakes a strategic review as to whether it should expand its range to include Chateau Woolfe, imported from France, or instead start exporting Stuber to the international market. How do these options stack up under the various tax proposals? For ease of analysis we assume that Bacchus Stores sells Stuber Estate and Chateau Woolfe for the same price and at the same profit margin. Impact of Trump’s proposals

The choice for Bacchus Stores is clear: sell domestically or export, then import. Impact of the House blueprint

The choice for Bacchus Stores is again clear: export first, and then sell domestically; only import if it can increase the price. As can be seen above, the House blueprint results in a vastly wider variation of potential outcomes and would be significantly more beneficial (in some cases resulting in tax credits) and punitive at the extremes than Trump’s proposals. From a policy perspective, the House blueprint provides much greater incentives to return production to the US and export than a relatively small import tax and a sizeable reduction in the federal rate under Trump’s proposals. |

In view of the potentially significant impact of the proposed reforms on individual companies, we believe that knowledge of a business, its cost base and supply chains is needed in order to determine whether it is likely to be a winner or a loser under a new US tax regime. Through in-depth knowledge of sectors and engagement with companies, supported by a detailed model that looks at a range of scenarios, we aim to identify the investment opportunities and risks that such a fundamental overhaul of US corporate tax will undoubtedly produce.

Any reference to a specific security, country or sector should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell investments in those countries or sectors.

Comments